Seoul Anniversary: When the Backstroke Went Rogue – How Underwater Power Changed the Event

When the Backstroke Went Rogue – How Underwater Power Changed the Event

On Sept. 24, 1988, the final of the men’s 100 backstroke at the Olympic Games in Seoul unfolded. The event featured underwater power never seen before.

*************************************

Call it a game of hide and seek, an approach that left the coaches and officials on the deck guessing as much as the spectators who occupied the venue’s seats. When would they surface? Who would come up first? What kind of advantage would be created? How much late-race damage would the strategy inflict?

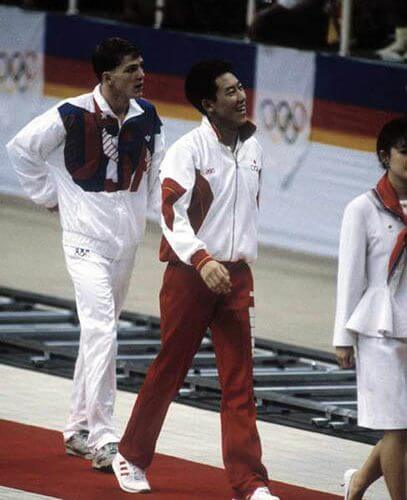

Daichi Suzuki and David Berkoff at the 1988 Seoul Olympics Photo Courtesy: Daichi Suzuki

It was at the 1988 Olympic Games in Seoul where Japan’s Daichi Suzuki, in a battle with American David Berkoff and the Soviet Union’s Igor Polyansky, raced to the gold medal in the 100-meter backstroke while submerged for nearly half of the race, including the opening 30 meters.

How that moment arrived is a tale in itself.

Ahead of His Time

When Jesse Vassallo’s career is measured, it is always viewed from a what-if standpoint. Although not alone in the robbery he experienced—with politicians serving as the thieves—Vassallo was among the most impacted individuals by the United States boycott of the 1980 Olympic Games in Moscow. As a triple medalist at the 1978 World Championships, with gold medals earned in the 200 meter backstroke and 400 IM, Vassallo was expected to go to Moscow and shine on his sport’s biggest stage.

Instead, Vassallo was victimized by the decision of President Jimmy Carter to use America’s Olympic athletes as political pawns. In protest of the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan, Carter somehow thought not sending an Olympic team to Moscow would send a message. And in a way, a message was sent: Carter basically suggested that the athletes’ years of dedication and hard work were meaningless.

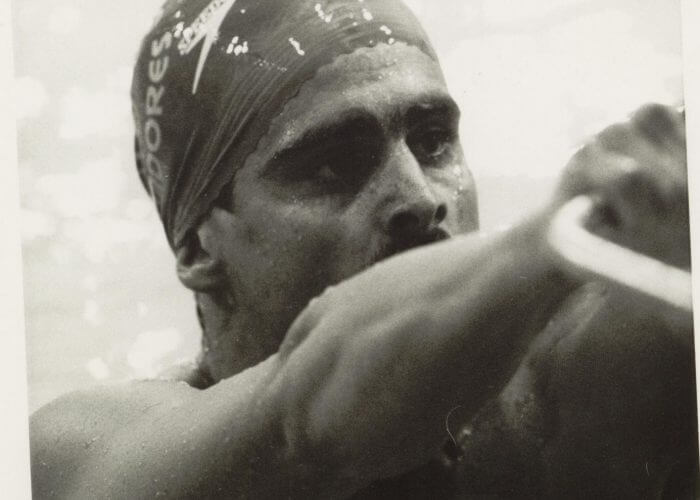

Photo Courtesy: Chris Georges

For Vassallo, who was at the peak of his career, the boycott robbed him of the opportunity to put forth the greatest performances of his career. Exacerbating the situation was the fact that his world-record time in the 400 IM would have won gold by more than two seconds, and his best time in the 200 back would have won the silver medal. Instead? Nothing.

As much as Vassallo is remembered for being denied the possibility of Olympic glory, he is also remembered as an innovator. In a sport frequented by giants, Vassallo was an anomaly, an athlete who could hold his own on the global stage despite standing only 5-feet-9-inches. The main negative of being on the small side—and in lanes next to more powerful swimmers—was being tossed around in his opposition’s wake. So, Vassallo got an idea.

“I decided to do the underwaters coming off the starts, and it worked pretty well,” Vassallo said in the documentary, How the Dolphin Kick Changed Swimming Forever. “After that, I continued to develop it and use it in my turns and stuff like that. I might be the one that originated and started this, but (others) really took it through to the Olympic level.”

The decision by Vassallo to utilize his underwater talent as an answer to a problem might have been innocent in its development. Ultimately, it eventually changed the sport.

A Game-Changing Innovation

The flirtation with an extended underwater approach may have proven beneficial for Vassallo, but it didn’t immediately catch on as a mainstream methodology. Still, there were a handful of athletes who dabbled with the tactic. Among them was Japan’s Suzuki, who raced underwater for the first 25 meters of the preliminaries of the 100 backstroke at the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles. Suzuki, though, failed to advance to the final, which consequently left his willingness to try a unique strategy temporarily lost on the rest of the world.

Daichi Suzuki launching into the 100-meter backstroke at the 1988 Seoul Olympics Photo Courtesy: Daichi Suzuki

While Suzuki did not benefit from his unorthodox style at the Los Angeles Games, Berkoff recognized the potential of extended time spent underwater. A solid backstroker when he started his Harvard University career under Coach Joe Bernal in 1985, Berkoff spent more and more time experimenting with the dolphin kick, learning that he was faster underwater than on top of it. With the new approach fueling him, Berkoff saw his performances quicken, to the point where he set an NCAA record in the 100-yard backstroke in 1987.

In the long-course pool, Berkoff honed his skill to a point in which he could remain underwater for 35 to 40 meters. Although oxygen debt certainly played a role for those racing underwater for lengthy periods, the advantage it provided offset the down-the-stretch struggles that arose. For Berkoff, the strategy led to a pair of world records at the 1988 United States Olympic Trials, where he became the first man in history to break the 55-second barrier in the 100 meter backstroke. After going 54.95 in prelims, Berkoff came back with an effort of 54.91 in the final, and he immediately became the man to beat for gold in Seoul, with the “Berkoff Blastoff” becoming his calling card.

“When I first did it my freshman year, a lot of coaches ridiculed it,” Berkoff said as a collegiate athlete. “They said, ‘You’re going to die the last lap.’ But I’ve expanded it every year. I don’t think it’s for everybody, but it’s going to change the whole idea of backstroke sprinting.”

Seoul Showdown

Once the 1988 Olympic Games in Seoul rolled around, extended underwaters were the norm, as footage of the 100 backstroke final shows five of the eight finalists surfacing beyond 25, and in some cases, 35 meters. But make no mistake. The final was undoubtedly a battle between Berkoff, Suzuki and Polyansky.

Following a world-record swim of 54.51 in the preliminaries, Berkoff reaffirmed his status as the favorite in the final. At the midway point, Berkoff was in control, the gold medal within reach off the strength of 35 meters underwater. But Suzuki and Polyansky were within striking distance, also having spent the majority of the first lap submerged.

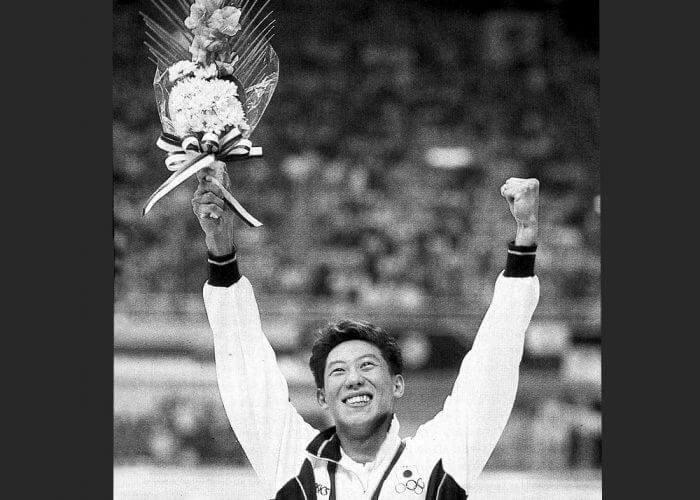

Daichi Suzuki with his gold medal on the podium at the 1988 Olympics Photo Courtesy: Daichi Suzuki

With each stroke, Suzuki and Polyansky closed the gap between themselves and Berkoff, with Suzuki pulling ahead in the final strokes to prevail in 55.05. The silver went to Berkoff (55.18), just ahead of Polyansky (55.20). Given his prelim performance, Berkoff’s setback was a surprise, the upset nature of sports revealing itself.

When Suzuki touched the wall ahead of Berkoff, thus completing his comeback triumph, he became the first Japanese Olympic champion in the pool since 1972. It was in Munich that Nobutaka Taguchi (100 breaststroke) and Mayumi Aoki (100 butterfly) stood atop the podium at a meet best known for the exploits of Mark Spitz and Shane Gould.

Suzuki has since gone on to hold several prominent roles in the sporting world, from president of the Japanese Swimming Federation to commissioner of the Japan Sports Agency. However, the future Hall of Famer still remembers the intensity of the moment in Seoul, and how he dealt with the pressure of an Olympic final.

“Just before starting the race, I transformed into a warrior,” Suzuki said in an Olympic Channel documentary. “In my mind, all I desired in that moment was to be No. 1. I was in the third lane. As you know, there is a short presentation (before the race), and you greet the public by waving. As I walked, I noticed that my legs were shaking, and I realized how nervous I was. Next to me, there was David Berkoff in the fourth lane. I saw his face, and he looked more nervous than me. It made me think I wasn’t the only one feeling nervous, so maybe I had a chance to win.”

Indeed, that was the outcome.

Suzuki may have captured the gold medal in the biggest backstroke showdown in Seoul, but Berkoff and Polyansky each earned a moment of their own on the top of the podium. While Berkoff led off the United States’ world-record-setting 400 medley relay in the second-fastest time ever (54.56), Polyansky captured the gold medal in the 200 backstroke.

Changing the Rules

Photo Courtesy: Swimming World Archive

Not pleased that the backstroke had become more of an underwater race than one that measured the athletes on their prowess in the discipline, FINA instituted a rule shortly after Seoul that limited backstrokers to 10 meters underwater off the start and turns. The decision, as soon as it was enacted, was a punishment for athletes like Berkoff, who had been revolutionary not just from an athletic standpoint, but from a creative perspective.

“I’m very upset by what FINA did,” said Berkoff of the ruling. “It’s completely ludicrous. It doesn’t really affect me because I decided a year ago that I would retire. But for future swimmers, the kids who started doing this, it’s a shame. I ruffled (FINA’s) feathers. They smacked me on the head. They said, ‘Things are not going to be as easy as you want, David.’ I did something to their game. I thought of it before they did.

“It was frustrating to put four years of your life on the line in Seoul, and after you’re so successful there, to turn around and say you can’t do that anymore is discouraging. That took a lot of trial-and-error and hard work. Their knee-jerk reaction was a slap in the face and an insult. That pushed me over the edge as far as getting out of the sport.”

In 1991, FINA changed the rule to 15 meters, and after three years of retirement, Berkoff returned to the sport and qualified for the 1992 Olympics in Barcelona. In his second Olympiad, Berkoff didn’t just capture a bronze medal in the 100 back, but proved he was more than an underwater performer and someone who found a loophole to reign among the best in an event. Rather, Berkoff was a phenomenal backstroker, both underwater and on top of it.

A Chapter to Remember

While Jesse Vassallo gently pioneered the extended underwater technique in the late 1970s and early 1980s, David Berkoff took the approach to its greatest heights in the late 1980s. Meanwhile, Daichi Suzuki also recognized the technique as highly beneficial, and used its adoption to become an Olympic champion.

Innovations in the sport will always be remembered. Goggles, starting blocks, lane lines and interval training have all influenced athletes’ abilities to get faster through the years. In the backstroke, it is critical to remember an era, although brief, that witnessed a handful of athletes take an outside-the-box approach toward improvement.

And how great it was to see Berkhoff’s daughter Katie capture the NCAA 100 back and the only swimmer under 50 seconds.

But didn’t Suzuki intentionally false start so that Berkoff would do his under water and not hear the recall, thereby exhausting him before the race actually began?

The history of swimming rules has been largely one of facilitating ever-faster times. What’s next? Many relay meets for years – York Y, PA, et al – have backstroke relays with swimmers 2-3-4 starting from a dive. SO fast, fun and easy! Why not have backstroke start from the blocks, with swimmers required to be on their backs when they surface within 15m? Swimmers love it, and the times are really fast!

Call me old fashioned…. but I like to see the fastest backstroker win the backstroke race… not the fastest underwater. I would happily see the 10m rule reintroduced- especially in short course.

These ‘innovations’ in stroke and technology – costumes/pools/ ledges create a false impression that swimmers are getting faster.

I think that it would be fun to add an Underwater race to the swimming lineup.