League of Olympic Swim Legends: Alex Popov Tops 50 Free With Hall Jr – Ervin, Biondi, Jager Snap For Bronze

What would have unfolded had Tokyo 2020 gone ahead as planned this week – and where would it all have fit in the thread of Olympic swim legends and pioneers like Alex Popov, Gary Hall Jr, Anthony Ervin, Matt Biondi and Tom Jager? To mark the eight days over which the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games would have unfolded had the coronavirus pandemic not forced postponement, the team at Swimming World is filling the void with a Virtual Vision Form Guide and League of Olympic Swimming Legends.

Day 8, event 1 – Fast and Furious …

Men’s 50m Freestyle

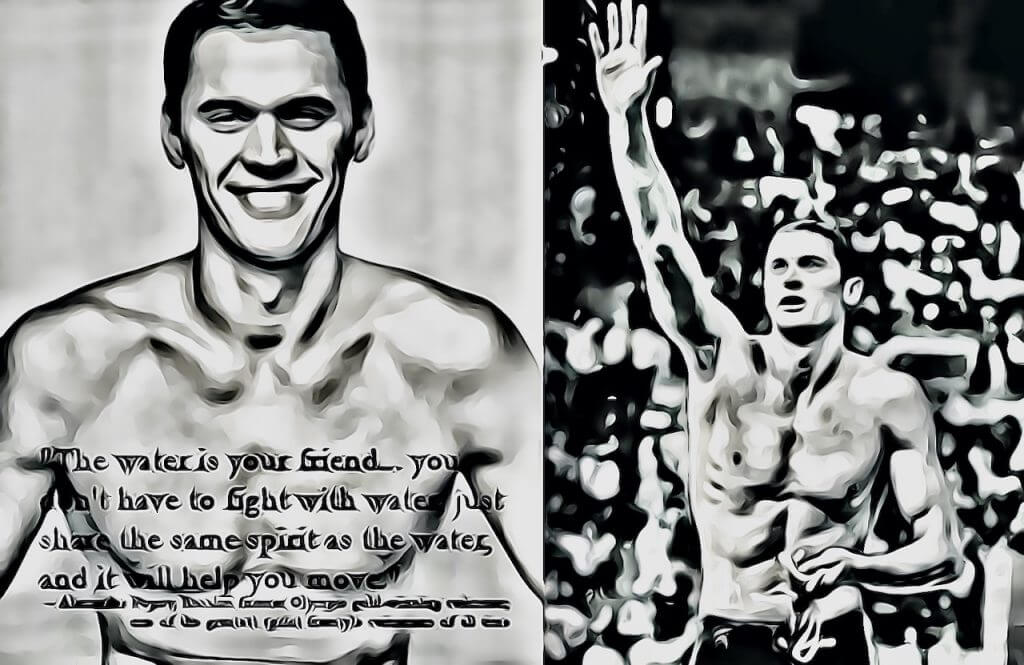

Alex Popov. Photo Courtesy: Patrick B. Kraemer

The Podium

- Alex Popov (RUS)

- Gary Hall Jr (USA)

- Anthony Ervin, Matt Biondi, Tom Jager (USA)

The Other Finalists (Listed Alphabetically):

- Cesar Cielo (BRA)

- Florent Manaudou (FRA)

- Zoltan Halmay (HUN)

Our Lane 9* place goes to the first man to appear on the World best time lists long after the 1956 rule that made long-course the official and, for over 30 years, the only standard of measuring pioneering speed … in other circumstances, he would have been in the 100m final with Montgomery in 1976 but he paid the price for his nation’s discrimination. Here we can add him to the league of legends, with a nod to the generations he has helped in the pool ever since:

- Jonty Skinner (USA)

* – in our series, we will use Lane 9 to add an athlete whose story reflects extraordinary situations of different kinds, including being deprived by those who fell foul of anti-doping rules or by political decisions or, indeed the Olympic program, as well as simple facts such as “he/she was the only other title winner who claimed gold in a WR but didn’t make out top 8 on points”

All-Time Battle Of Olympic Swim Legends Goes To Alex Popov

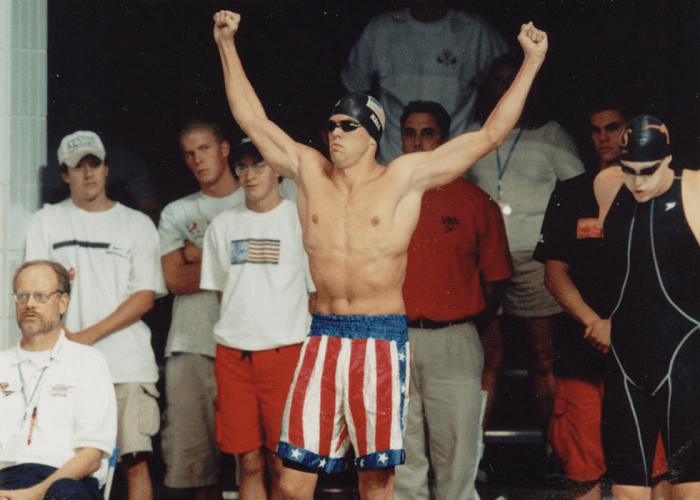

Gary Hall Jr at 2000 Olympic trials – Photo Courtesy: Peter Bick

Anthony Ervin – Photo Courtesy: Rob Schumacher, USA Today

Have you been counting down to see who came out on top as the fastest man in history?

If you’ve been waiting to see Russia’s Alexander Popov on the top step of the podium, your wish has been granted. Step up undefeated 1992 and 1996 champion sprint freestyle.

Popov gave his 1996 Olympic gold medal for the 100m to his coach Gennadi Touretski as a token of thanks, saying:

“I have a title and I’m on the result sheet, but Gennadi didn’t get anything from Atlanta, nor from Barcelona. I know how much this particular medal means for him, what it’s worth to him.”

Matt Biondi – Photo Courtesy: ISHOF

In Moscow 30 days later, Popov was stabbed in the stomach after intervening in a fight between a friend and a watermelon seller. The knife penetrated 15cms, damaging the pleura, the membrane that encases the lungs, missing a kidney by the edge of a blade and slicing an artery. Emergency surgery was followed by three months in rehabilitation.

The incident changed his life: Popov was baptised in an orthodox church shortly after the stabbing. He recovered well enough to defend the European sprint titles at Seville in 1997, when he described the process of overcoming adversity in these terms:

“My soul wasn’t damaged, my brain wasn’t damaged, only my body.”

He spoke at a press conference in Seville at which Craig Lord asked him about recovery, the healing power of water and his relationship with the element in which he excelled. His reply entered the lore of the sport:

“The water is your friend, you don’t have to fight with water, just share the same spirit as the water, and it will help you move. If you fight the water it will defeat you. We were born in water – it’s like home to me.”

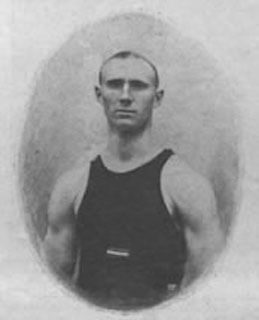

Tom Jager in 1986 – Photo Courtesy: Swimming World Magazine

In our Legends battle of the ages, Popov turned away some of the best names in the event, including Matt Biondi, Gary Hall Jr. and Tom Jager. The Tsar’s world record of 21.64 took down a 10-year-old standard and lasted for seven-plus years.

The tussle for the silver medal was tight, but Hall Jr. and his Olympic golds of 2000 (shared with Anthony Ervin) and 2004 gave the longtime sprint standout the nod over Biondi. Hall was aided by a silver medal at the 1996 Olympics, and his win in 2000 came at the expense of Popov. That Hall and Popov share the podium is fitting, given spectacular their rivalry and disdain for one another.

At the helm of those surging to win the battle for bronze was Biondi, who won the 1988 title ahead of Jager and added a silver medal four years later in Barcelona. Biondi registered three world records and, as a pantheon of 11 Olympic medals, eight of them gold and 5 of the medals in solo events demonstrates, he did his best work when the pressure was on.

In this battle of the ages, Ervin lagged Biondi all the way until the closing five metres. In the furious hunt for the end wall, Ervin relied on three reserves in his tank: the Olympic title he shared with Hall Jr. as a 19-year-old at Sydney 2000, which put him in the race to start with, the longevity of his journey of excellence and; how that came out in Olympic waters (so far), namely Rio 2016 gold as the oldest champion in history, at 35.

Ervin also made the final at the 2012 Games, and one can only wonder what he might have done if he didn’t leave the sport for seven years after the 2003 World Championships.

Ervin has no World solo records to his name but a span of five Olympic Games with golden bookends all events – 2016 also giving him the record for the most years between gold medals – provided fuel enough for him to place his hand on the wall precisely at the same time as Biondi. A snap for bronze.

And this is where we, the judges, roll back the years, hail the naked eye of yore, ignore the electronic timing on the day, and take into account the Olympic fight and the spirit that transcends the moment.

Jager never did get his hand to the wall first in an Olympic final: he claimed silver behind Biondi in 1988 and then bronze behind Popov and Biondi in 1992. Here are two factors we feel deserve to be taken into account in our battle of the ages virtual world: the World records and pioneering pace-setting of our legends and what happened next after the day did not go as best it could have done.

Jager set six world records, was the first man to go sub-22 and had a 13-year reign as World record holder and left the standard at 21.81. In 1990! It took 10 years and Popov to take it down.

Then there is this: what does a Team Captain do when he’s tried and tried and tried again, picked up World titles, set the pace for others but in Olympic waters finds silver converted not to gold but bronze. Well, his coaches and some teammates thought they would not see Jager for a while after that moment in Barcelona that for many would have been a most joyful occasion to take on into the rest of life but for the American speedster was crushing.

Jager understood: he was the captain of a team. He showered, put on his team kit, returned to the stand and spent the rest of the day and meet cheering for his teammates. And that represents the true golden nugget in the Olympic spirit right there. As such, we feel, for the purposes of this exercise, a three-way tie for bronze, putting Jager up there with Biondi and Ervin is a good way of reflecting the qualities that it also takes to be a legend.

Any minded to protest: get your Swiss francs out! 🙂

Meanwhile, in this age of living in our times, even the likes of Alex Popov and Matt Biondi fading into history, many appear to think the Olympic 50m freestyle was born in 1988. Not so. The one name in our legends line-up that many may not recognise is that of Zoltán Halmay, of Hungary: he won the 1904 dash title and his Olympic story is summed up at the foot of this feature.

Alex Popov – The Phases of Freestyle:

The Olympic Victories of Alex Popov

1992 Barcelona – Men 50m Freestyle – Athletes: 75 Nations: 51

- 21.91 Alexander Popov RUS

- 22.09 Matt Biondi USA

- 22.36 Tom Jager USA

22.50 Christophe Kalfayan FRA

22.50 Peter Williams RSA

22.52 Mark Foster GBR

22.54 Gennadi Prigoda RUS

22.73 Nils Rudolph GER

Date of final: July 30, 1992

USA team-mates Matt Biondi and Tom Jager had been the two giants of 50m sprinting for as long as the one-length blast had been made an official event at the 1986 World Championships.

In Seoul, it was gold for Biondi, silver for Jager, beyond which Jager would set a world record of 21.81 in 1990 that would last for a decade until the standard was broken in 2000 by Alex Popov. By then, the Americans had long-since retired. Before they did so, they would feel the new force of the man who would come to b e known as the Sprint Tsar.

Popov made his international debut at the European Championships in Athens, 1991, but while he won the 100m title in 49.18sec, he did not compete in the 50m and remained the mystery man on one-length sprinting by the time he arrived in Barcelona, compared with the 26-year-old title favourites, Biondi and Jager.

Popov was a pretender no more in the 100m after stopping the clock at 49.02sec to win the 100m title, with Biondi back in fifth. Two days later, Popov became the first man in Olympic waters to race inside 22sec over 50m, his 21.91 ending the reign of the Americans, Biondi second in 22.09, Jager third in 22.36. The race(s):

1996 Atlanta – Men 50m Freestyle – Athletes: 64 Nations: 57

- 22.13 Alex Popov RUS

- 22.26 Gary Hall USA

- 22.29 Fernando Scherer BRA

22.33 Chengji Jiang CHN

22.59 Brendon Dedekind RSA

22.68 David Fox USA

22.72 Francisco Sanchez VEN

22.73 Ricardo Busquets PUR

Date of final: July 25, 1996

Alex Popov breezed into the 1996 Olympic Games with top billing in the freestyle sprint events, with 1992 Olympic and 1994 World 50 and 100m titles in the pantheon.

In 1996, the host nation had found a new weapon in the shape of Gary Hall Jr., son of Gary Hall, who in the era of Mark Spitz had set nine world records, a record eight of them on medley. At the 1994 World Championships, Hall Jr, finished second to Popov in both the 50m and 100m finals.

The same pattern would take shape in Atlanta in 1996, though the gap between king and pretender was much narrower in both events.

Two days after matching American Johnny Weissmuller’s 1928 feat of retaining the 100m crown – with a 48.74 win by just 0.07sec over Hall Jr – the Russian raced level with the American to 40m in the dash final.

In the closing 10m, the Russian opened up a solid 0.13sec edge to win the crown in 22.13. That would be the end of Popov’s winning days in Olympic waters,. though he would make the podium in 2000 and the race in 2004.

For Hall Jr., Atlanta marked a debut that would lead on to shared gold in 2000 with USA team-mate Anthony Ervin and gold alone at Athens 2004.

Gary Hall Jr – Gold Alone At Athens 2004

Gary Hall – Photo Courtesy: ISHOF

2004 Athens – Men 50m Freestyle – Athletes: 83 Nations: 74

- 21.93 Gary Hall

- 21.94 Duje Draganja CRO

- 22.02 Roland Schoeman RSA

22.08 Stefan Nystrand SWE

22.11 Jason Lezak USA

22.18 Brett Hawke AUS

22.26 Oleksander Volynets UKR

22.37 Salim Iles ALG

Date of final: August 20, 2004

At the 2003 World Championships, double-double Olympic Sprint freestyle champion of 1992 and 1996 and 100m silver er medallist of 2000, Alexander Popov became the king of longevity. He was 31 when he claimed the World titles, yet again, over 50m and 100m.

The question was clear: could the Sprint Tsar span four Olympic podiums from Barcelona 1992 to Athens 2004?

The painful answer – no – was delivered on August 19, three days shy of the 13th anniversary of Popov’s stunning international debut in Athens, 1991, when he had won the European 100m crown in a continental record while racing at his first and last event as a swimmer of the Soviet Union.

Alex Popov greeted his passing with grace after clocking 22.58 for shared 18th place in heats, 0.03sec shy of a place in the semi-finals. His reign was over.

Anthony Ervin and Gary Hall Jr. shared gold in the 50 freestyle at the 2000 Olympics.

At the helm of qualifiers was his arch-rival and defending champion Gary Hall Jr, on 22.04. He backed that up with a 22.18 in the semi-final but found himself fifth-best going into a final, with lane four filled by Roland “The Blade” Schoeman, a member of the victorious South African 4x100m freestyle relay quartet that had upset the USA and Australia four days before.

In the final, Schoeman got the perfect start, off his blocks with a reaction time of 0.62sec, the best by 0.01sec ahead of Jason Lezak, and 0.09sec up on Hall Jr, with Duje Draganja, US-based Croatian, in the middle on 0.69. The finish was too close for the human eye to call: the scoreboard confirmed that Hall Jr was champion in 21.93, 0.02sec outside the 1992 Olympic record set by Alex Popov back in 1992, but 0.01sec ahead of Draganja, with Schoeman taking bronze in 22.02.

With that victory, Gary Hall had finally broken through, past his silver-linings in Popov’s wake, past shared gold with teammate Anthony Ervin in 2000 to a place all of his own at the top of the ultimate peak for Olympic swimmers.

Matt Biondi Settles An Argument For Olympic Gold In A World Record

Matt Biondi – Photo Courtesy – Swimming World Magazine

1988 Seoul – Men 50m Freestyle – Athletes: 71 Nations: 44

- 22.14wr Matt Biondi USA

- 22.36 Tom Jager USA

- 22.71 Gennadi Prigoda URS

22.83 Dano Halsall SUI

22.84 Stefan Volery SUI

22.88 Vladimir Tkashenko UKR

23.03 Frank Henter FRG

23.15 Andrew Baildon AUS

Date of final: September 24, 1988

There could have been no better place than Madrid for the inaugural world-title races in the 50m freestyle to unfold: 30 years earlier, at Melbourne 1956, Spain called for the sprint event to be recognised as a world-record event and to be reintroduced to the Olympic programme (a 50-yard event was raced at the 1904 Games).

The proposal was rejected.

In Madrid, the inaugural men’s title went to Tom Jager, in 22.49. For men, FINA had set a time limit of 22.32 for the start of official world records, 0.01sec inside the world best time held by Matt Biondi.

By the time the Americans lined up for the Olympic final in 1988, Jager had won 10 out of 14 races with Biondi. But Biondi was said to have raced inside 22.33 at the USA national team camp more than 50 times that summer. Whether he did or not, the result in Seoul proved his superiority under pressure: he claimed the crown in 22.14 to Jager’s 22.36.

In April that year, Peter Williams, a South African training in the United States but locked out of international competition and beyond eligibility for the world record because of his nation’s apartheid policies, clocked 22.18.

In Nashville, on March 24, 1990, Jager became the first man inside 22sec with a 21.98sec heats swim before a 21.81 in the final. The mark would stand until until June 16, 2000, when Alex Popov clocked 21.64. On February 17, 2008, Eamon Sullivan swam 21.56. In two further leaps, the Australian left the mark at 21.28 on March 28 while wearing one of a new generation of bodysuits that helped to improve speed across the world, particularly in events up to 200m.

The First Olympic 50m Free in 1988? Try 1904.

Zoltán Halmay – Photo Courtesy: ISHOF

1904 St. Louis – Men 50m Freestyle – Athletes: 9 Nations: 2

- 28.0 Zoltan Halmay HUN

- 28.6 J. Scott Leary USA

- 29.2 Charles Daniels USA

29.8 David Gaul USA

30.4 Leo Goodwin USA

31.0 Raymond Thorne USA

Date of final: September 6, 1904

Zoltan Halmay, the first Olympic 50 and 100 yards freestyle champion, took on Charles Daniels, the man credited with teaching American crawl to the world, for the first time at the 1904 Games in St Louis.

A day after Halmay had beaten a final full of Americans in the 100y, the silver going to Daniels, the Hungarian won the 50y by a clear margin but the American judge declared home hero Scott Leary the champion. Leary fanned the flames by claiming that the Hungarian had interfered with his line of swimming.

Zoltán Halmay – Photo Courtesy: ISHOF

A brawl broke out on the lakeside and lasted for the best part of an hour. Eventually, a tie, at 28.2sec, was declared and the race was re-swum. After two false starts, Halmay led from start to finish, winning the crown in 28.0sec to Leary’s 28.6sec. Daniels was third. The race marked the last time that Daniels would be defeated by Halmay in a long rivalry.

By 1904, Daniels, then aged 20, was already dominant over distances of 200yd and more. At St Louis, he took his tally of medals to five, with victories over 220yd and 440yd and as a member of the USA 4x50yd freestyle relay, a race omitted across many Olympic references.

Daniels defeated Halmay once more at the Intercalated Games of 1906 that were never recognised by the IOC. Between 1907 and 1911, Daniels set seven world records, two of those were over the 100m and 200m freestyle, as pertaining to the official records era under the auspices of FINA.

He and Halmay would meet for the last time at the 1908 Olympic Games in London, where Daniels won the 100m crown in a world record of 1:05.6, 0.6sec ahead of the Hungarian.

The World In 1904: