Memories of Moscow 1980: The Highs & Lows Of Living An Olympic Dream You Should Never Give Up On – By Glen Christiansen

Memories of Moscow 1980, the 40th anniversary of 22nd Olympic Games in Moscow, where Glen Christiansen lived his Olympic Dream, a notion that comes with thrilling highs and crushing lows, underpinned by a message to a generation dealing with the postponement of the Tokyo 2020 Games: never give up on your own dream.

Swimming World continues its 40th anniversary coverage of the events of Moscow 1980 and their impact on those who missed out and what the Moscow Games meant for those who made it, even, in some cases, when their Governments did not endorse their participation but their nations did.

Moscow 1980

Our Moscow 1980 Olympics coverage so far

- The Michelle Ford Story, Part One: The Phone Call From Her Mum That Changed Michelle’s Life Forever

- The Michelle Ford Story, Part Two: The Plan That Sank The GDR Machine And Hate Mail On The Biggest Day Of A Swimming Life

- Memories of Moscow 1980: Why Rica Reinisch Had To Retire At 15 After 3 Olympic Golds & 4 World Records

- Memories of Moscow 1980: When Sweden’s Pär Arvidsson Led A Podium Of Historic Firsts Over 100m Butterfly

- Memories of Moscow 1980: 40 Years On, Mary T. Meagher Shares Memories of Olympic Boycott

- Memories of Moscow 1980: 40 Years To The Day Since Vladimir Salnikov Cracked 15-minute Barrier Over 1500m Free

- Memories Of Moscow 1980: How Duncan Goodhew Converted Olympic Gold To Victory In Life

- Memories of Moscow 1980: When Barbara Krause Took 100 Free Below 55sec 20 Years Before Her Day In Court With Kipke

- Memories of Moscow 1980 – When Sergei Fesenko Became The First Soviet Swimmer Among Men To Claim Olympic Gold

- Memories of Moscow 1980 – 40 Years Since Boycott Buried The Chances Of Cheryl Gibson & Maple Mates

- Moscow Olympic Flagbearers Max Metzker And Denise Boyd Linked Forever In Australia’s Proud Olympic History

- USOPC CEO Sarah Hirshland to 1980 Olympic Team: ‘You Deserved Better’

- The Moscow Boycott: A Toxic Mix of Sports and Politics Proved Costly for Hard-Working Athletes

Living the Olympic Dream at Moscow 1980 – By Glen Christiansen

In this week of the 40th anniversary of the Moscow Olympic Games, which coincides with the postponement of the Tokyo Olympic Games, my own Olympic experience of trauma and joy rises to the surface. I was an Olympic swimmer, an Olympic camp manager and an Olympic coach.

And Yes, true. I was much more fortunate than my fellow US breaststroke friends like Glenn Mills and Jeff White who´s Olympic tickets were snapped away even before they could get on the plane. I actually made it to Moscow but just to have the Olympic Gold fly away even before I could dive into the pool and race for it.

But let me try to tell you a long story in a short way if you care to read. It is a story of tears and frustration and a story of joy and laughter. It is my Olympic story.

My Olympic dream didn´t start at an early age of 8 – 10 years like many hopeful swimmers around the world. No, I started swimming late at the age of 13 with sporadic training and it wasn´t until I was 14,5 years old I understood what swimming is about. The coach of our group quit coaching and we 20 odd kids were moved up to the senior group which were coached by Berndt Nilsson. There were around 40 swimmers in this group, some who were training for the Olympics and some like myself who could hardly make a flip turn with a best time of 1.30” for the 100m breaststroke.

But coach Berndt was an ex-military, strong, tall, ice blue eyes, a man with a firm hand, which is exactly what little Glen needed.

Coach Berndt (himself an Olympic breaststroker) woke my Olympic dream by telling me to set a goal with my swimming (which I replied by saying that I wanted to be the best in the world) and letting me train with the Olympic swimmers. That and my father’s advice:

“With hard, continuous work and a strong belief in yourself you can reach any goal”.

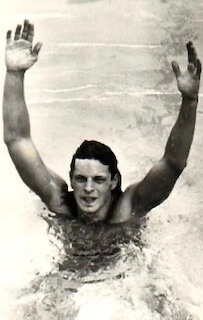

Glen Christiansen in 19872 at 15, at Swedish Nationals in Boras, Gunnel Weinas, famous coach to Olympic diving legend Ulrika Knape to his right (left in the shot) – Photo Courtesy: Glen Christiansen

The next summer I went to the Swedish senior Nationals despite not having made the qualifying time, slept in a tent outside of the arena and made the finals. Two years later at the age of 17 I won the Swedish senior national championships with a new Swedish record in the 100m breaststroke and were selected for the National team. The year after I won 3 Gold at the national championships and the sky was the limit. I trained harder and harder and got better and better.

The Olympic Games in Montreal were coming up the next year and I wanted to win! But as many swimmers before and after me I trained too hard that Olympic year. I swam hell weeks with 14.000m Breaststroke every day, bicycled back and forth from home to school to work hours and got a key to the pool so that I could swim when I wanted. Which was always. I won the Swedish Olympic trial but my time was not good enough and I wasn’t selected for the Olympics.

What a flop!

Here I was going for the Gold and didn’t even qualify! I was extremely disappointed and sad. I wanted to quit swimming but then decided to give it a go for the Moscow 1980 Olympics four years away. To get better training and competition challenges I accepted a scholarship in the US and took my first flight over the Atlantic.

In the US I learned racing more often and harder, training long and fast and positive attitude and strong team spirit. I am eternally grateful to the coaches who led me to the next Olympic challenge; Phil Hansel, David Kintas and Dick Jochums.

At 20, Glen Christiansen was Swedish chamois over 100, 200 and 4x100m medley with teammates – Photo Courtesy: Glen Christiansen

One morning in March 1980 Coach Jochums came out on the pool deck and told us that President Carter had decided to boycott the Moscow 1980 Olympic Games.

Emptiness.

That is what I felt. And deep disappointment.

For my teammates and my friends. Sweden would not boycott holding a neutral stand. But as grateful I was for that I still felt deeply disturbed. But I told myself to keep the focus on my own training and racing the best I could.

In April a month later at the US Nationals in Austin Texas I made the final in the 200m breaststroke, took a second place in the consolation final of the 100m breaststroke with a new Swedish record and our 400m Medley relay team with Bob Jackson, Steven Gregg and Doug Northway broke an US Open record. I swam a 1.04 on that relay, a very promising time for the Olympics.

Even better: my Swedish friend Pär Arvidsson broke the world record in the 100m butterfly. We both looked forward very much to swimming the 400m Medley relay together in Moscow. The preparations for the Olympics went on in Sweden and on camp in Finland. We all showed good form and spirits were high.

One of the freestylers, Pelle Holmertz had a foot injury during the camp but since we had two strong freestylers on the team, the other being Per Johansson, (they both won silver and bronze later in the Olympic final) we were not worried. Another thing that had to be resolved was that we didn’t have two A cut times in the 100m breaststroke (but in the 200m yes) so we could only have one swimmer participating in the 100m breaststroke.

What would I prefer? The 100m breaststroke or the relay? An easy choice for me being an extreme relay swimmer and knowing the medal chances were much better in the relay than the individual start. So we agreed on Peter B, five years younger than me, swimming the 100m and 200m breaststroke and me swimming the relay and the 200m breaststroke.

Cal alumni and Olympic swim champions Pär Arvidsson and Matt Biondi in 2017 – Photo Courtesy: Cal Swim & Dive, Twitter

At the Olympics, always expect surprises and upsets. On the first swimming day of the Moscow 1980 Games, our teammate 18 year young Bengt Baron swam a fantastic final and won the 100m backstroke surprising the world! Teammate Pär Arvidsson repeated his strong swimming in the 100m butterfly and also won the gold! Suddenly we were not talking only medals for the Medley relay! We were talking GOLD, having the Olympic champions in 100m backstroke and in 100m butterfly and the Olympic silver medalist in the 100m freestyle and the wild breaststroker relay specialist Glen. Little Sweden with a population of 8 million could and “should” win the 400m medley relay. For the first – and perhaps the last – time in history.

What happened next I do not recall 100 per cent because I was not involved in the discussion but the leaders and coaches met and decided to swim with a B team in the prelims. Like the Americans do. To swim with backstroker # 2, breaststroker #2, butterflyer #2 and Pelle Holmerz checking his form after the foot injury. I remember saying I would prefer to swim the prelims too. I think Bengt said the same thing. We didn’t need to rest up for the final but ended up being told to stay in the Moscow 1980 Olympic village, rest and get psyched up for the final watching the prelims on a black and white television with a poor signal.

We did just that – and saw that the B team easily qualified for the final as 4th or 5th. But what we didn’t see was that the breaststroker had false-started, in his inexperience and excitement: the team was disqualified.

For me it is important to say that I do not blame Peter. He was an 18-year-old swimmer who didn’t have much experience of relays (Sweden is not the US where they race in relays all the time) and maybe he didn’t get clear enough directives from the coaches just to swim the team safely into the final.

Regardless of the why’s and wherefores, Sweden lost its only chance ever to win the 400m medley relay – and I lost a medal without even having a chance to swim for it. The next day, I swam the 200m breaststroke heats: I raced 3 seconds slower than my best, placing 11th. I tried to harness “revenge” as motivation but my spirit was gone. I knew I would never have that chance again.

My Olympic dream was gone.

It took 16 years for me to get rid of the knot in my stomach and the sweating as soon as anyone asked me about the Olympics.

I stopped swimming for a couple of months but with help from my coaches Jan Wingfors and Kerstin KP Pettersson, as well as the encouragement of Bengt Baron, I made my return, started swimming again and made changes to my training.

I had the best summer season in my life that year: I ended up in swimming a 1.01.60 short-course 100m breaststroke, the fastest time in the world that year (mind you, without ‘fly kicks off the walls and without dipping the head below the surface). But the Moscow 1980 was a scar yet healing and the next Olympics were far away. I stopped swimming at the age of 25, that making me the oldest in my club team and on the national team.

There were no short-course Worlds or Europeans, no World Cups, no ISL, no way to have any economic support of the kind that exists today.

A Lifetime Of Coaching & A New Olympic Dream

Lecturing in Germany – Photo Courtesy: Glen Christiansen

When I started coaching, my co-coach Ing-Marie Nilsson and I were blessed with coaching one of the best talents Sweden ever had, Ann Linder. Two years later, she was my first Olympic swimmer. Four years later, I was asked by the German Olympic team and the Swedish Olympic team to organize their Olympic camps for the Seoul Olympic Games, which I did, at different locations in Japan.

But what about that knot in the stomach and the sudden sweats? Well, to finish off this long story with a short summary:

The lump in the stomach disappeared on July 22nd 1996 in Atlanta, Georgia during the Olympic Games as my German swimmer Antje Buschschulte won a bronze medal. I hugged her in the warmup pool after the race, crying a bit with relief – and the knot, the lump in my throat: gone.

It all made sense to me.

I didn’t win that Olympic medal because I was destined to coach swimmers to win medals. I was representing and coaching Sweden but had swimmers from Germany and Ireland on my team too.

The Olympic dream. Fulfilled.

For the Olympic Games in Tokyo I sent in a request for being a Volunteer at the Games hence having my 4th role in the Olympic dream. Having lived 5 years in Tokyo knowing the city, it’s people and still remembering some Japanese I was really looking forward to this. I feel sad for the athletes and the coaches but can only give them encouragement and the advice: do not give up on your Olympic dreams. It can still come through. Maybe not in the way you expected or hoped for but it can come true.

If you do not give up on your dream!

Interesting article Glen Christiansen ???? Helena McGrath