Memories of Moscow 1980: Why Rica Reinisch Had To Retire At 15 After 3 Olympic Golds & 4 World Records

Today marks the 40th anniversary of the fourth day of racing in the pool at the 1980 Olympic Games in Moscow, where Rica Reinisch, 15, claimed triple gold for the GDR, set the World 100m backstroke record three times and the 200m standard once … on the way to a doctor’s surgery to hear news that her swimming career would have to end because of medical complications related to the steroids she had been fed from an early age by the architects and overseers of State Plan 14:25.

Swimming World continues its 40th anniversary coverage of the events of Moscow 1980 and their impact on those who missed out and what the Moscow Games meant for those who made it, even, in some cases, when their Governments did not endorse their participation but their nations did.

Moscow 1980

Our Moscow 1980 Olympics coverage so far

- Memories of Moscow 1980: When Sweden’s Pär Arvidsson Led A Podium Of Historic Firsts Over 100m Butterfly

- Memories of Moscow 1980: 40 Years On, Mary T. Meagher Shares Memories of Olympic Boycott

- Memories of Moscow 1980: 40 Years To The Day Since Vladimir Salnikov Cracked 15-minute Barrier Over 1500m Free

- Memories Of Moscow 1980: How Duncan Goodhew Converted Olympic Gold To Victory In Life

- Memories of Moscow 1980: When Barbara Krause Took 100 Free Below 55sec 20 Years Before Her Day In Court With Kipke

- Memories of Moscow 1980 – When Sergei Fesenko Became The First Soviet Swimmer Among Men To Claim Olympic Gold

- Memories of Moscow 1980 – 40 Years Since Boycott Buried The Chances Of Cheryl Gibson & Maple Mates

- Moscow Olympic Flagbearers Max Metzker And Denise Boyd Linked Forever In Australia’s Proud Olympic History

- USOPC CEO Sarah Hirshland to 1980 Olympic Team: ‘You Deserved Better’

- The Moscow Boycott: A Toxic Mix of Sports and Politics Proved Costly for Hard-Working Athletes

Rica Reinisch – Photo Courtesy: CL/NTArchive

Ina Kleber – Photo Courtesy: NT/CLArchive

By the time 15-year-old Rica Reinisch jumped in the waters of Moscow’s Olympic pool for the final of the 100m backstroke 40 years ago this day, she had already equalled and then improved on the World record twice. Leading off the GDR 4x100m medley relay to a World-record victory on the first day of action, she produced a 1:01.51 match of 1976 Olympic champion Ulrika Richter’s global standard. Then she made the mark her own, splitting the difference between her and her fellow East German by 0.01sec, on 1:01.50.

Dominance followed: in the final, a 1:00.86 in the final delivered gold with an improvement and speed that matched that made by Dawn Fraser over 100m freestyle between 1958 and 1960 on her steady way down below the minute by 1962.

We will never know whether Reinisch might have travelled a similar trajectory on the clock had she been a healthy swimmer after Moscow. By the time the Berlin Wall fell in late 1989 and systematic doping State Plan 14:25 moved on to appear in other form and place, just one woman, also East German, had surpassed her 1980 winning speed: Ina Kleber, who went to Moscow in 1984 instead of Los Angeles because of a retaliatory boycott and clocked 1:00.59.

The World titles of 1982, 1986 and 1991 all went to swimmers racing outside Reinisch’s top speed, while her 1:00.86 Olympic record of Moscow would survive the 1984 and 1988 Games before Hungarian ace Krisztina Egerszegi shave 0.1sec off the standard in morning heats on July 28 at Barcelona 1992 on her way to a 1:00.68 victory later in the day.

A different era, under different rules with different equipment and it is quite easy to think that Reinisch, who looked like a swimmer just setting out towards full potential in 1980, might have been the first woman inside the minute all those 40 years ago. A flip turn staying on her back, no goggles, no starting wedge … yet, 1:00.86, the drive off the turn wall worth watching for the power it granted her over rivals who didn’t stand a chance, East Germany teammates Kleber and Petra Riedel on 1:02.07 and 1:02.64 respectively as the only others inside 1:03.8:

Rica Reinisch And The Salvation Of A Doctor’s Diagnosis

Thankfully, for Rica Reinisch, her health, welfare and the thread of truth in world swimming history, a doctor intervened and a different history unfolded, though not one void of the same issues generated by State Plan 14:25 long after the result sheet, a stack of Stasi (state police) archives confirming the crime and the wilful blindness of the guardians and governors of sport were all that was left of it.

Reinisch followed up her medley relay and 100m gold medals with a World-record victory in the 200m backstroke, her 2:11.77 shaving 0.16sec off absent American Linda Jezek’s World record and making her the only woman in swimming history to break four solo World records at a single Olympic Games.

Her encore was not to be. When Reinisch left Moscow she was suffering from serious stomach pains. Her coach Uwe Neumann, who had given her “little blue pills in a chocolate box”, took her to see a Dr Loeffler at a Dresden clinic. The doctor explained to her that she was suffering from inflammation of the ovaries, caused by high dosages of steroids given to her since before puberty. Reinisch was instructed not to mention this to her parents or family doctor.

She had become an Olympic champion and victim of State Plan 14:25. Almost two decades later, in 1999, Reinisch spoke to reporters during the German doping trials in which several coaches and doctors, including Neumann and Lothar Kipke, former FINA Medical Commission member and keeper yet of the international federation’s Silver Pin honour for services to the sport, were convicted of bodily harm to underage athletes.

In the ensuing interviews Reinisch pointed to the many things that saddened her, among them a longing to know who she was. She said:

“What makes me sad is that I will never know how good I could have been.”

Back To The Roots Of Talent & Torment

Grossschönau nestles in beautiful countryside in the district of Görlitz, the lovely Saxon town where Hotel Budapest was filmed. The border with the Czech Republic skirts the old town. Back in the day, the place was a famous Upper Lusatian centre of Damask fabric production but that collapsed with the Berlin Wall. Today, tourism is the greater draw in a region blessed with the romantic landscape of Saxon Switzerland to the west, the Lausitz region, where the wolf was reintroduced a decade or so back, to the north and the Iron Mountains, best known for Germany’s wooden Christmas decorations, its nutcrackers, incense-smoking figurines, wooden pyramids and the like.

Reinisch was born there and, from a young age after having been measured for sports suitability at 6, was placed in a sports school in Dresden, about an hour and half’s drive away.

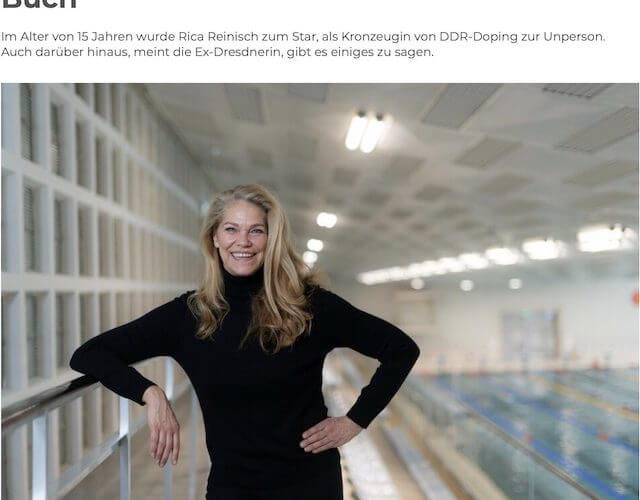

She lives far away these days, in Eschweiler in the Rhineland far west in the old West behind a Wall that divided families and friends for all too long. Now 55, she is married and has two grown children, Marcel, 35, and Nastasia, 33. Her husband, Harald Klein, is a renowned German interior designer. Reinisch trained as a journalist years after her sporting triumphs and these days shares her time between the press office that works for her husband and a role as a mental-strength coach to people who need help untapping hidden potential.

Experience of the realm she has in abundance.

Of late, she’s thrown herself into a third activity: as a member of the Lions Club “Eschweiler Stolberg” and the “Wasserfreunde Delphin” swim club, she runs a scheme that teaches socially disadvantaged children and unaccompanied refugee children how to swim.

“The children who can already swim and develop a talent for it will be integrated into the club,” Rica Reinisch told the Sächsische Zeitung this year. The Lions Club finances a part of the scheme, which is being rolled out in nearby Aachen, with the help of a local children’s home and SV Neptun Aachen.

Reinisch gets back to Saxony for annual holidays and on family visits, her mother, aunt and two cousins still living in Großschönau, her brother Dirk in Dresden.

There’s a sense of sadness in the words of Reinisch when she speaks of her homeland, especially in relation to Dresden, the once-bombed out but now restored and beautiful city where she trained at a time when much had not been repaired, the building were brown and grey and the pools were places of work. Hard work.

The Sächsische Zeitung ran a headline this year that caught my eye:

“Why Dresden has forgotten its best swimmer”.

The article, by Alexander Hiller, started by inviting the reader to:

“Imagine Dynamo Dresden (the local football club) listing the best players in the club’s history and, for example, failing to mention Dixie Dörner or Ralf Minge (two of its most famous players in history). The outcry would be inevitable. Due to their outstanding skills and successes, both deserve to be counted among the people who, without a doubt, go through as club legends.”

Missing Portrait

Rica Reinisch, right, with medley relay gold medallists of the GDR, from left, Caren Metschuck, Andre Pollack and Ute Geweniger , Photo Courtesy: SZ ragout

Rica Reinisch swam for SC Einheit Dresden, where only the diver Ingrid Gulbin-Krämer had a bigger Olympic medal count, with three golds and a silver at the 1960 and 1964 Games. The diver’s achievements are on the Wall of Fame at Dresden’s new 50m swimming complex in Freiberger Straße. There is Krämer, all smiles and with her medals a must in what the local paper calls “our ancestral gallery”. Reinisch is missing – and has been for decades.

Reinisch has been a persona non grata in Dresden circles since she first spoke out about what she endured in the early 1990s after the Wall had fallen. She was also a key witness in the Doping Trials of 1998-2000 and cooperated on the telling of truth in books such as Brigitte Berendonk’s “Doping – From Research To Deception”.

Rica Reinisch told the Sächsische Zeitung that she suspects that her revelations about systematic doping, which was an integral part of the Dresden program in her day, have led to her being ostracised. She said:

“I think that gave the impression that [speaking out] harmed us or wanted to harm us. I don’t understand that.”

She also notes that the current club still celebrates the successes of a time they know the place was a part of the centralised system that operated State Plan 14:25.

In a 2018 interview with the same newspaper, a club official noted:

“I believe that the Dresden SC is also proud of that time … and that there is increasing opposition to the general suspicion that sporting success in the GDR is equated with state doping. That was so: it’s an historic fact.”

He then utters words likely to find opposition in waves across the world: “The success of the GDR sport was primarily due to the quality of the coaching, the scientific support and the simple realization that you were privileged if you were successful.”

The “quality of coaching” meant feeding steroids to 11-13 year olds like Reinisch, of course.

Söllner added: “We do not suppress our past and we face up to discussion where there is one. However, we are not pursuing any initiative to review the club’s history.”

Neither the club nor the pool are responsible for who makes the “wall of fame”. That’s down to the Stadtschwimmverband Dresden, the city swimming association, the boss of which in 2018, Steffen Böhmert, told the SZ:

“It is not an issue that Rica should be a [part of the wall of fame] up there.” He then acknowledges, as the SZ put it “the upheavals that Reinisch caused with her doping revelations after reunification led to the estrangement of both sides”. A former GDR swimmer, Böhmert adds:

“There has been no contact for more than 20 years, we never got a picture of her …”

He noted that Rica Reinisch must give her consent for her photo to be used these days: “Rica would have to give her unequivocal consent. This is not possible due to the data protection regulations.”

A weak argument, says Rica Reinisch:

“That argument is huge: my portrait was hanging up there earlier – nobody had asked for my consent beforehand. My wonderful brother Dirk, who lives in Dresden, made me aware in the mid-1990s that I’d been removed from the gallery.”

She points out that she gave data permission to the DSV, the German Swimming Association (which adopted all the DDR’s records after reunification in 1990) for use of her pictures. As such, there would have been no impediment to Dresden asking either the DSV or, indeed, her.

Reinisch is not the only missing swimmer. Frank Wiegand, who won Olympic silver in 1964 over 400 meters freestyle and three other Olympic silver medals with GDR relay teams, is now 77. He was GDR athlete of the year in 1966.

Rica Reinisch – Photo Courtesy: SZ ragout

Rica Reinisch Will Publish Her Story

Rica Reinisch is unrepentant. The truth will out. She is penning her story in a double autobiography with former volleyball player Petra Schreiber, who competed in West Germany. The aim is to show the differences and similarities in the experience of the two women.

Says Reinisch:

“I am currently sitting and writing. Petra tells how she grew up in western Germany, me from my East German perspective. We discovered astonishingly many parallels, there were a lot of synergies.”

“Since I’m forcing myself to deal with my past, a lot of memories come back from childhood and youth.”

Advertising: Shop At Swim360

I’m enjoying this expose. How many parts total?