Memories of Moscow 1980: 40 Years To The Day Since Vladimir Salnikov Cracked 15-minute Barrier Over 1500m Free

Today marks the 40th anniversary of the third day of racing in the pool at the 1980 Olympic Games in Moscow, where Vladimir Salnikov became the first man to race under 15 minutes for the first of his two Olympic titles over 1500m freestyle against a backdrop of politics and boycott, life-changing chances seized and stolen.

Swimming World continues its 40th anniversary coverage of the events of Moscow 1980 and their impact on those who missed out and what the Moscow Games meant for those who made it, even, in some cases, when their Governments did not endorse their participation but their nations did.

Moscow 1980

Our Moscow 1980 Olympics coverage so far:

- Memories Of Moscow 1980: How Duncan Goodhew Converted Olympic Gold To Victory In Life

- Memories of Moscow 1980: When Barbara Krause Took 100 Free Below 55sec 20 Years Before Her Day In Court With Kipke

- Memories of Moscow 1980 – When Sergei Fesenko Became The First Soviet Swimmer Among Men To Claim Olympic Gold

- Memories of Moscow 1980 – 40 Years Since Boycott Buried The Chances Of Cheryl Gibson & Maple Mates

- Moscow Olympic Flagbearers Max Metzker And Denise Boyd Linked Forever In Australia’s Proud Olympic History

- USOPC CEO Sarah Hirshland to 1980 Olympic Team: ‘You Deserved Better’

- The Moscow Boycott: A Toxic Mix of Sports and Politics Proved Costly for Hard-Working Athletes

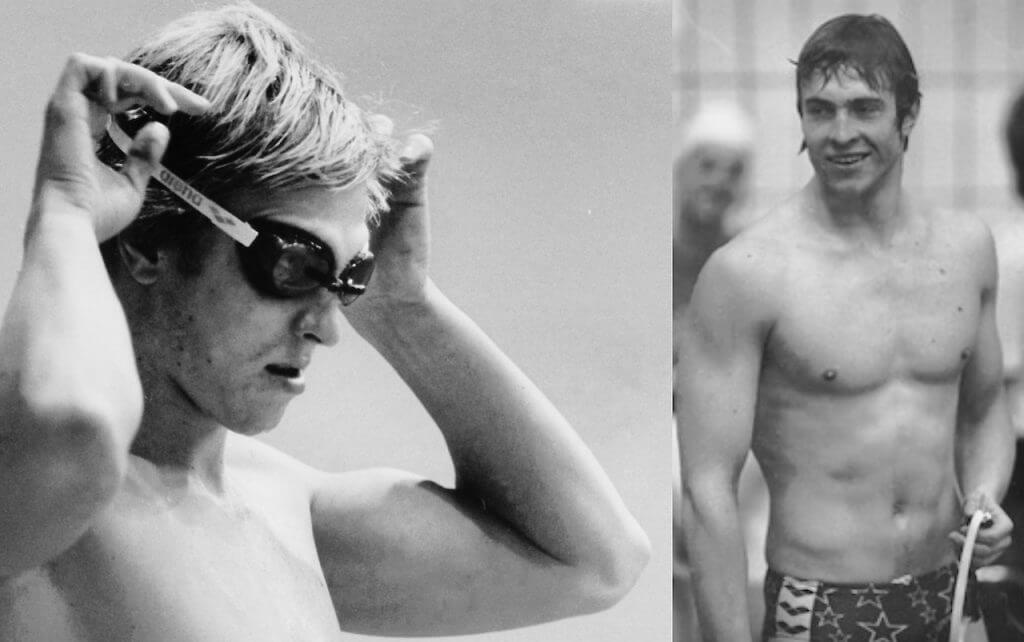

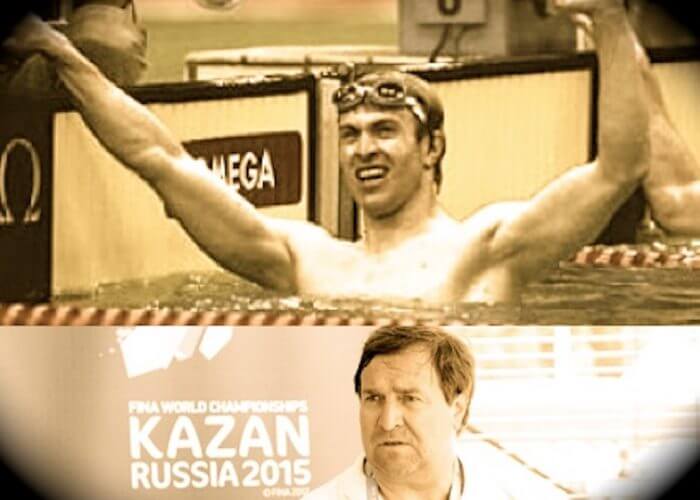

Vladimir Salnikov – Photo Courtesy: Bob Martin, Allsport / Swimming World Archive

July 22, 1980, goes down in history as the day Vladimir Salnikov broke the 15-minute barrier over 1500m freestyle. If racing at an average speed of less than 1-minute for every 100m was a first it was not the only one for Salnikov that day: in claiming Olympic gold for the hosts of the Moscow 1980 Games, he became the first Soviet winner of the 30-length race since it all began in 1896.

To be precise, the waters of “1500m” racing at the Olympics are a little muddier: out at sea in the Bay of Zea near Pireaus in what were reported to be 12-foot waves, about 1,200m were covered a race of just two men, Hungarian Alfred Hajos the champion in 18 minutes 22.2, the Greek challenger Ionnis Andreou on 21:03.4. The first official 1500m race in a pool was at London 1908, when local hero Henry Taylor claimed the crown after 15 lengths of the first and only Olympic pool that was 100m long. His time: 22:48.4, the first World Record recognised by FINA, which was formed on the eve of those Games at the Manchester Hotel in London.

Salnikov was a bit quicker. In 14:58.27, he took down the World record that had stood to American Brian Goodell since he claimed Olympic gold at Montreal 1976 in 15:02.40 at the helm of what remains to this day one of the most thrilling 1500m races in history. His teammate Bobby Hackett took silver in 15:03.91, the bronze to Australia’s Stephen Holland in 15:04.66. Then came Brazil’s Djan Madruga on 15:19.84, before a 16-year-old Salnikov, on 15:29.45.

That marked the first of Salnikov’s seven European records over 1500m (and one of 22 continental standards he established during his career). He never lost a European final over 1,500m, winning in 1977, 1981 and 1983. At 15, he took his last silver over 1,500m, at the European junior championships.

Four years after his Olympic debut and with much work packed in, the 20-year-old Salnikov travelled 2sec per 100m faster, on average, as a home crown raised the rafters at the glass-bound-surround “Olympiiski ” pool.

Sadly, boycott meant that there was no Goodell there to defend the crown and we will never know what might have been. What we do know is that Salnikov and Goodell had not been strangers since 1976.

The son of a sea captain in Leningrad, Vladimir Salnikov was taken to a local swim club at 8 to learn how to be safe. At 9 he joined the Zenit training squad and later entered the Armed Forces Sports Society. He was spotted by Igor Koshkin, who coached the swimmer to world-class status and was responsible for ensuring that his young charge knew his enemy: Salnikov trained for a short spell at Mission Viejo in California with coach Mark Schubert alongside Goodell and Tim Shaw (1975 world 200, 400 and 1,500m champion), a swimmer whose own ‘what if’ was delivered by illness in Olympic year 1976.

How Vladimir Salnikov Led What Would Remain The Fastest 1500 Field Until 1996

The day after Salnikov’s Moscow victory, The New York Times reported that Salnikov had beaten Goodell’s time of 1976 by “an astonishing 4.13 seconds”. In the context of Olympic 1500m racing, 4sec was not, in fact, “astonishing”: it amounted to about 0.13sec per length in an event that had seen improvements between Games of 50sec 1972-1976; 47sec 1968-72; 23sec 1964-68…

Had Goodell and others been there that day, the race may have gone down as one of the greatest in swimming history. As it turned out, it was all about Salnikov and the 15-minute barrier. The silver went to his Soviet teammate Aleksandr Chayev in 15:14.30, a touch ahead of Australia’s Max Metzker, on 15:14.49 (after 6th on 15:31 just behind Salnikov four years earlier), with the GDR’s Rainer Strohbach locked out in 15:15.29 in the fastest 1500m field ever seen to that date, the third Soviet swimmer in the final, Eduard Petrov, last home in 15:28.24. In sixth, Rafael Escalas, of Spain, was, with Metzker, the only non-Soviet bloc swimmer in the race. The final was completed by Yugoslavia’s Borut Petric, in fifth, and Hungarian Zoltán Wladár.

Little appreciated down the years is just how fast that entire field was in the context of its time and place in history: if Salnikov’s 1980 pace would survive the 1984 Games, and the 1988 Games at which he would claim gold once more before facing the sledgehammer of a 14:43.48 World record from Australian Kieren Perkins for gold at the 1992 Games, then the pace of the Moscow 1980 field would not be surpassed until Perkins led the 1996 final to his own second gold.

The first sub-15-minute qualification for an Olympic 1500m freestyle unfolded at Beijing 2008 in the first season of shiny suits that would be banned from January 1, 2010 because of the significant artificial boost and skew delivered by non-textile apparel.

Defending two-time champion Grant Hackett, of Australia set an Olympic record of 14:38.92 in heats, while Canadian Ryan Cochrane set an American record; Russian Yuri Prilukov set a European record and Zhang Lin of China an Asian record, American Larsen Jensen last through to the showdown in 14:49.53.

Though it has happened at World Championships, the first sub-15-minute final has yet to happen, seven men under but the last man home over at each of the past three Olympic Games, 2008, 2012 and 2016.

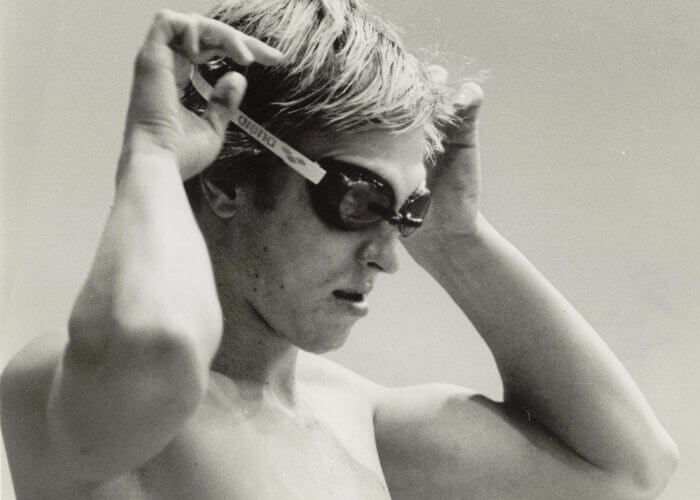

Vladimir Salnikov in 1983 – Photo Courtesy: Ladislav Perenyi / Swimming World Archive

In Moscow 40 years ago, Salnikov – who would become known as “Monster of the Waves” in a nod to his toughness and a tilt at the swell in which “the longest” race got underway back in 1896 – led throughout, going through the first 100m in 58.53, compared to Goodell’s 58.59 at Montreal 1976.

After his opener, Salnikov unfurled his masterpiece with repetitions of between 60.04 and 60.79sec, turning at the 500m mark in 5:00.23, setting a European record of 8:00.40 at the 800m and flipping over in 10:00.85 at 1,000m. A last 500m split of 4:57.42 delivered the world record of 14:58.27.

Where Goodell had a race on his hands throughout, Salnikov was racing the clock. His slowest split was at the 1,100m mark but 100m later, the ‘Monster of the Waves’ knew the crown was his, the only thing remaining for him to know was how fast he had been travelling. Speaking to reporters through a translator after the race, Vladimir Salnikov said:

”When I passed 1,200 I was sure I would be first. But I was not sure I would break the record. When I passed the 1,400 (in 14:00.22), I thought I could break it.”

Addressing several questions about the absence of Goodell and the American team, Salnikov avoided guessing what others might have achieved. Staying in his own lane, he noted:

”If the United States swimmers were here, I’m sure the timing would be exactly as I’ve done today.”

He declined to discuss his specific training, other than to say that he spent ”four or five hours a day” in the pool, while altitude training had been a part of his regime and that, he believed, had “played a large role in my preparation”.

Vladimir Salnikov came to wider prominence in aquatic circles after his Olympic debut, when he set a European record to win the 1977 European title in 15:16.45. A year later, he claimed both the 400 and 1,500m World titles in Berlin, both in European record times. Come spring 1979 he was ready to set the global pace: he broke the first two of 13 world records, the first in Minsk in March, with a 7:56.49 800m that made him the first man to break 8mins, the second a month later in East Berlin, his 3:51.41 400m taking 0.15sec off what would be the last World record of Goodell’s career, in August 1977.

Between March 1979 and July 1986, Salnikov dominated distance freestyle, setting 13 world records over 400m (6, including 1 equalled), 800m (4) and 1,500m (3), his time at the helm of times interrupted only by Peter Szmidt (CAN), on 3:50.49 in July 1980 (absent from boycotted Moscow 1980). In 1982, at World Championships in Guayaquil, Salnikov became the first man to claim both the 400 and 1500m crowns.

The Shadows Cast By Events

The world swimming community understands well the drop of boycott and what it deprived athletes and the sport of in 1980. The American decision hurt American athletes first and foremost, though the politics of Soviet invasion of Afghanistan and Western reaction to it had an impact on many beyond the United States.

As Neil Admur noted in The New York Times when explaining the impact Vladimir Salnikov and that first sub-15-minute swim over 30 lengths:

“It was a big dream of the Americans to have the first man under 15 minutes,” observed Birger Buhre, the former head of the Swedish national swimming team. ”This was a very special race.”

Doping was a whisper becoming a breeze at the time, each race the GDR women’s team won resulting in more discussion about the nature of success of a team of teenage girls sporting the hallmarks of androgyny. When that discussion stretched to Soviet athletes being asked about doping, Buhre, whose son attended the University of Alabama at the time, told The New York Times:

”I’ve seen the Russians in training. They were well prepared. And there is no doping.”

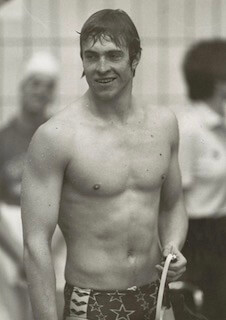

Rica Reinisch – Photo Courtesy: CL/NTArchive

A Times report followed that assertion with this: “Eastern European athletes, including swimmers, have been accused of using drugs to aid athletic performances in the past. Salnikov’s effort could have carried the third day of swimming. But Rica Reinisch of East Germany continued to rewrite the 100 backstroke records, this time lowering the standard to 1:01.50. Miss Reinisch’s world record, by only one one-hundredth of a second, came during a semifinal, so an even faster time seems likely tomorrow in the final. The extent of the East German dominance of the events for women was reflected by their 1, 2, 3 sweep in the 400 freestyle final.

“The race was interesting only because the three women – Ines Diers, Petra Schneider and Carmela Schmidt – fought so intensely. Miss Schneider, who was expected to battle Tracy Caulkins of the United States for medal glory before the American boycott, led after 100 (59.57), 200 (2:01.86) and 300 meters (3:05.12).”

Back to the Buhre quote and it is, undoubtedly true that Eastern European athletes were “well prepared”: the regime of East German swimmers was among the toughest, if not the toughest, in the world. It included pioneering approaches to the sport, cross-training including cross-country skiing, pool decks fitted with pulley systems and markers linked to pace clocks so that swimmers could know precisely how fast they were travelling in specific timed sets in training.

Some would cover 16-20km a day in the pool, not just once in a while but most days of the week, recovery helped by the thing that made the workload possible: Oral Turinabol and other “supporting means” at the heart of the State Plan 14:25 systematic doping regime unleashed on an estimated 10,000 athletes across many sports.

The state police of East Germany, the Stasi, wrote it all down, including names and dosages and the timing of it all. So, we know – and some of what we know made it to court between 1998 and 2000 in the German doping trials that handed swathes of coaches, doctors, scientists and politicians criminal convictions for abuse of minors. Supplying doping to minors in Germany these days is a criminal offence punishable by a prison sentence.

Vladimir Salnikov’s Magnum Opus Was Yet To Come

Photo Courtesy:

Victory for Vladimir Valeryevich Salnikov this day 40 years ago marked the first of three gold medals at the Moscow 1980 Olympics, the 400m freestyle and the 4x200m freestyle completing the set.

If Salnikov’s pioneering pace of 1980 sampled his ticket to the club of sporting immortals, it was his Magnum Opus eight years on, beyond another Olympic boycott, one that locked him out of Los Angeles 1984, that sealed his universal acclaim and recognition.

There was no sub-15-minutes in 1988 but a 15:00.40 kept at bay Germany’s Stefan Pfeiffer, on 15:02.69, the bronze to the GDR’s 400m champion Uwe Dassler, on 15:06.15, leaving the 1976 podium still the fastest in history before the 1992 final would write a new line.

When Salnikov walked into the athletes’ dining hall in the Olympic village in Seoul 1988 a little shy of midnight on September 25, 1988 – medal ceremony, drug testing, media interviews and television appearances out of the way – some 300 fellow competitors, coaches and officials from all sports spontaneously laid down their cutlery and gave a standing ovation in his honour.

Salnikov, who would later in life join the FINA Bureau – the board of the international federation – remained the only man to win a solo Olympic swimming title at least eight years apart until Americans Michael Phelps (200m butterfly, 2004, 2008, 2016, silver in 2012) and Anthony Ervin (50m freestyle, 2000, 2016) at the Rio Olympics of 2016.

At his fastest, Salnokov got down to 14:54.76 in Moscow in February 1983. In 1989, Glen Housman, of Australia, clocked 14:53.59 but the electronic timing failed and his time was never ratified as a world record. Jorg Hoffmann (GER) went down in history as the man who broke the Russian’s record, his 14:50.36 win at 1991 world titles in Perth keeping another budding giant at bay, a teenage Kieren Perkins, of Australia, just 0.22sec away.

The Pain Before Gain Again

The biggest losses of Salnikov’s career unfolded during his preparations for the 1988 Olympic Games. That led to many a pundit writing him off. Having won 61 consecutive 1,500m races between 1977 and 1986, Salnikov, who from 1984 was coached by his wife, Marina (a former Soviet national track and field record holder over 100m and a sports psychologist), found himself locked off the podium in 4th at the 1986 world championships in Madrid.

He finished 13sec behind West German winner Rainer Henkel. The following year, Salnikov failed to make the final at the European Championships, and in Olympic year Soviet coaches ruled him out of contention, his place in Seoul only secured by the intervention of the Soviet Sports Ministry. Time magazine wrote:

“Salnikov’s long day [at the top] … has passed. He can expect nothing more in Seoul than to see the last of his records fall in front of him.”

In Seoul, Vladimir Salnikov laid down an unexpected gauntlet with a 15:07.83 heats effort. Only Matt Cetlinski (USA) was faster. In the final, the American led for 13 lengths before Salnikov drew up and went on to lead for the last 800m. A late challenge from West German Stefan Pfeiffer was not enough to keep Salnikov from his date with destiny.

Salnikov made history that day as the only man ever to win the same Olympic swimming title eight years apart and at 28, as the oldest champion since 28-year-old Yoshiyuki Tsuruta (JPN) retained the Olympic 200m breaststroke crown at Los Angeles 1932.

After retirement from racing, Salnikov lived in Spain for several years before returning to Russia, where he has been president of the Russian Swimming federation for more than a decade. For part of that time, his right-hand man was Alex Popov.

In Other Action, day 3, Moscow 1980

Duncan Goodhew takes gold in the 100m breaststroke form Great Britain: the five-ringed Olympic flag was raised instead of the Union Flag, and the Olympic hymn was played instead of ”God Save the Queen” during the award ceremony because Britain was among 16 countries that chose to march under Olympic or National Olympic Committee flags at the Opening Ceremony in Moscow to protest the Soviet military invasion of Afghanistan. Goodhew wore the Union Flag, his national colours and sang the National Anthem on the podium (without being threatened with suspension or loss of medal) before telling reporters:

”I’m still British, and I still believe in my country. I believe I swam for my country in the Olympic Games.”

The Globe and Mail noted at the time:

“Goodhew’s ceremony was shown on Soviet television in prime time and is likely to intensify debate about the coverage of events related to the Afghanistan issue. Cameras had closely followed the traditional flag-raisings for Salnikov and Miss Diers of East Germany earlier in the evening. But pictures of Goodhew on the victory stand, spectators waving a Union Jack from their seats and even the band playing the Olympic hymn were shown before a flag-raising shot that lasted no longer than three seconds. Only a Soviet viewer keenly familiar with the Olympics could have realized the significance of the occasion. The sight of the Olympic flag, flanked on each side by national flags from the Soviet Union and Australia, which was divided over team participation, underscored the politics.”

The women’s 400m freestyle went without World champion and record holder Tracy Wickham, of Australia, and American podium placers behind her at 1978 World titles in West Berlin, Sippy Woodhead, then just 14, and Kim Linehan.

Moscow 1980 – Day 3 Results

Men

100m breaststroke:

- 1, Dunkan Goodhew, Britain, 1:03.34

- 2, Arsen Miskarov, U.S.S.R., 1:03.82

- 3, Peter Evans, Australia, 1:03.96

- 4, Alexandr Fedorovsky, U.S.S.R.,1:04.00

- 5, Janos Dzvonyar, Hungary, 1:04.67

- 6, Lindsay Spencer, Australia, 1:05.04

- 7, Pablo Restrepo, Colombia, 1:05.91

- 8, Alban Vermes, Hungary, disqualified.

100m butterfly – Qualifiers for semifinals 1, Par Arvidsson, Sweden, 55.18; 2, David Lopez, Spain, 55.54; 3, Kees Vervoorn, Netherlands, 55.76; 4, Evgeny Seredin, U.S.S.R., 55.83; 5, Roger Pyttel, East Germany, 55.99; 6, Xavier Savin, France, 56.07; 7, Gary Abraham, Britain, 56.10; 8, Guy Goosen, Zimbabwe, 56.15; 9, David Lowe, Britain, 56.22; 10, Philip Hubble, Britain, 56.30; 11, Miloslav Rolko, Czechoslovakia, 56.36; 12, Alexei Markovsky, U.S.S.R., 56.45; 13, Sergei Kiselyov, U.S.S.R., 56.56; 14, Fabrizio Rampazzo, Italy, 56.85; 15, Gabor Meszaros, Hungary, 56.88; 16, Boguslaw Zychowicz, Poland, 57.21

1,500m freestyle –

- 1, Vladimir Salnikov, U.S.S.R., 14:58.27 WR

- 2, Alexandr Chaev, U.S.S.R., 15:14.30

- 3, Max Metzker, Australia, 15:14.49

- 4, Rainer Strohbach, East Germany, 15:15.29

- 5, Borut Petric, Yugoslavia, 15:21.78

- 6, Rafael Escalas, Spain, 15:21.88

- 7, Zoltan Wladar, Hungary, 15:26.70

- 8, Eduard Petrov, U.S.S.R., 15:28.24.

Women

100m backstroke – Qualifiers for final 1, Rica Reinisch, East Germany, 1:01.50 WR; 2, Ina Kleber, East Germany, 1:02.15; 3, Carmen Bunaciu, Romania, 1:03.25; 4, Petra Riedel, East Germany, 1:03.25; 5, Larisa Gorchakova, U.S.S.R., 1:03.82; 6, Monique Bosga, Netherlands, 1:04.36; 7, Carine Verbauwen, Belgium, 1:04.37; 8, Manuela Carosi, Italy, 1:04.42.

400-Meter Freestyle – Final

- 1, Ines Diers, East Germany, 4:08.76 (Olympic record; old record, 4:09.89, Petra Thuemer, East Germany, 1976)

- 2, Petra Schneider, East Germany, 4:09.16

- 3, Carmela Schmidt, East Germany, 4:10.86

- 4, Michelle Ford, Australia, 4:11.65

- 5, Irina Aksyonova, U.S.S.R., 4:14.40

- 6, Annelies Maas, Netherlands, 4:15.79

- 7, Reggie De Jong, Netherlands, 4:15.95

- 8, Olga Klevakina, U.S.S.R., 4:19.18.

From The Archive – Rio 2016

August 2016, by Craig Lord

It’s Vladimir Salnikov Vs Shirley Babashoff As Events Sir The Ghost Of Cold War In The Pool

Shirley Babashoff Cornelia Ender and Enith Brigitha 1973 – Photo Courtesy – NT/CLArchive

The echo from history stood out in twitterdom for the clarion call it was:

@_king_lil you are #MAKINGWAVES and we love it! Go girl- you are what the world – and ESPECIALLY what the Olympics need right now. #HONESTY – Shirley Babashoff

Along that slice of history calling came another: FINA Bureau member and Russian swim federation boss Vladimir Salnikov, twice an Olympic 1500m freestyle champion for the Soviet Union (1980 and 1988) and a contemporary of Babashoff at the 1976 Olympics, today said that the atmosphere surrounding his team in Rio reminded him of the Cold War.

He criticised American 100m breaststroke champion Lilly King for “attacking the integrity of her Russian rival”, apparently having forgotten the 2013 positive steroid test for which Yuliya Efimova was banned.

Efimova has been booed and jeered every time she rise to her blocks and Salnikov tells Reuters, the news agency:

“I think the whole atmosphere is very strange.”

Salnikov appeared to be out of step with history in the making, however. Here at these Games, Michael Phelps said he was “pissed” that convicted dopers were allowed to compete, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) announced that its president Thomas Bach backed lifetime suspensions from the Games. His coach, Bob Bowman, said that he felt the authorities had “dropped the ball” on doping.

All of that unfolds at a time when the state’s involvement in doping in Russia is being held up as reminiscent of the GDR’s State Plan 14:25. However, Salnikov views the situation differently.

Vladimir Salnikov – Photo Courtesy: Maria Dobysheva

The atmosphere at the Rio Aquatics Centre reminded him of “when we had the situation with the Cold War and everything was like Russia (versus) America and a lot of people were putting oil on the flame to make it higher. This is another round, but I think we will survive it.”

Salnikov, who leads a federation that has yet to explain to the World Anti-Doping Agency why two EPO positives among teenage swimmers in 2009 were not reported, said that King was entitled to her opinion but noted that Efimova had legal backing of the Court of Arbitration for Sport, which ruled in favour of Russian swimmers threatened with exclusion from Rio 2016 as part of the inquiry into the Russian doping crisis .

“Does she consider the CAS decision is wrong?” asked Salinkov, adding: “She has a long road to go in sport, I hope, and I think in the end she will understand there are certain rules, there’s a procedure that regulates the participation of athletes. Of course she has the right to her opinion, but you need to be objective and you need to be honourable.”

And then came the sympathy not for the athlete defeated by another who fell foul of rules but for the rule-breaker instead:

“Efimova has been through a very severe ordeal, and in an atmosphere of distrust and uncertainty I think she showed very strong character – resilience and focus – and so I think she deserved her medal. She has come through very tough times and I’m sure she will cope.”

Making Waves – Shirley Babashoff – Santa Monica Press

Back to Making Waves and Shirley Babashoff. Clobbered in the pool by State Plan 14:25 and thumped in the media for speaking out when she mentioned the muscles the burley maidens in the next lane, reached out to Lilly King with a message that reminded us why athletes who support Fair Play and clean sport are getting ever more agitated and unprepared to stay silent.

The IOC is said to be seeking a way of rewriting the ‘Osaka’ rule in a way that would keep dopers out of the Games for life.

Lifetime bans are fraught with legal difficulties, the IOC has suggested. There is a change of mood, however, according to IOC spokesman Mark Adams:

“The President (IOC, Thomas Bach) said that for serious doping issues, he would still really like to see a life ban. There are a number of options we can look at that would certainly I would imagine be one of them but this is all very much within a very difficult legal framework. It is something that the President is very keen on and it appears that the public is very keen on it is just a matter of finding a way that is legally sound.”

Why would a lifetime ban be fraught with difficulties?????? Sound legalities????? Come on. Haven’t we heard this same blah blah blah since 1976? Why are the guilty athletes defended and the clean athletes vilified for speaking the truth?

Quite so – the skill is to make clear what offences constitute a lifetime ban … the Olympic movement has no trouble being autonomous when it wants to be… so, if you signed up to club rule X and you then break them and cannot win an appeal against such judgment, there should be no impediment to you being shown the door for the length of time stated in the rules you signed up to (including lifetime bans which already ARE a part of the WADA Code and ARE enforced…)