Kiphuth’s Ride to the Medal of Freedom: Part VIII; A Showcase for Swimming — Yale Water Carnival

As seen through the eyes of Chuck Warner, Swimming World Contributor

NEW HAVEN, Connecticut, September 20. THIS is the eighth column in a series of columns about the history of swimming. The sport's only Presidential Medal of Freedom winner was Robert John Herman Kiphuth. The famed coach at Yale University was selected for the prestigious award by President Kennedy. Just prior to Coach Kiphuth receiving this award in December of 1963, the President was shot and killed. We are presenting some snapshots of swimming history as thoughts that Coach Kiphuth might have had driving to the Medal of Freedom ceremonies.

Kiphuth weaved his car through the maze of New York skyscrapers driving ever closer to Washington D.C. These highways were familiar to him. He regularly ventured to New York City for monthly AAU meetings as he worked to advance the sport of swimming. He liked driving fast and moving forward in life. Any traffic congestion might have irked him. If his thoughts trailed back to 1932 the coach might have considered the contrast between the achievements of completing the fabulous Payne Whitney Gym that year, with the struggle that the American men had at the Olympics.

The 1932 Games were held in Los Angeles and the Japanese men dominated the overall Olympic swimming competition of the standard six men's events. The American women ruled the pool in their five-event program. By the 1936 Games in Berlin, Germany, world-wide tension was mounting as Adolf Hitler rose to power with his Nazi regime and served as the host for the quadrennial celebration of the sport of swimming. The Japanese again dominated the men's events while The Netherlands did the same in the women's five-event program. The Dutch flew up and down the pool collecting four of the five gold medals, while the USA could only garner two bronze.

As much as he asserted himself through the AAU and other committee work there was only so much control that Coach Kiphuth could have over The American Swimming Team's destiny, but at Yale he had enormous control. Their new facility could showcase the sport like the world had never seen.

Kiphuth's dynasty in Yale dual meets was building toward his eventual career won-loss record of 528-12. While spectators enjoyed the Yale meets with local schools, the world of swimming came to attention each year with the initiation and growth of the amazing annual Yale Water Carnival.

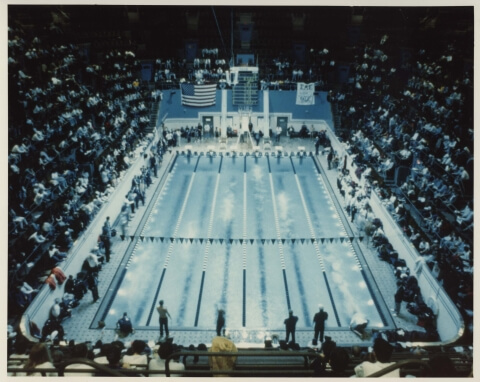

Photo courtesy Yale

The Water Carnival was conducted in the greatest swimming theatre on Earth, the Yale Exhibition Pool. The construction included a 53-foot ceiling, unobstructed views and the capacity to turn off all the overhead lights and leave on the underwater lights to create a unique ambiance that even Broadway couldn't match. In an instant, the glow of lights could be the backdrop underneath a world class water ballet performance. Flip another switch and the facility was completely dark, except for the lights of red “exit” signs and a water polo game with florescent painted balls whizzed around the pool.

ISHOF's Bruce Wigo talks to SwimmingWorld.TV about the Yale Water Carnival

The Exhibition pool was the perfect venue and Coach Kiphuth was the perfect producer and director. He managed to attract the best aquatic performers in the world and put together a program that motivated people to pay admission for every one of the 2,187 seats. The world would quickly take notice and come to know the Yale Pool in the same way that Kiphuth expert Coach Pete Kennedy documents in his research and writing as “The World Record Pool.”

Once each year on Saturday night students, faculty, staff and area fans would get dressed in their best outfits, go out to dinner and then fill the world's greatest spectator arena for swimming. Money was raised for the Yale team, but more importantly Kiphuth's water show raised awareness and respect for a sport like no one had ever done before. At 8:15 p.m., the show began.

During the next several years the Carnival featured music provided by the Yale Band, the Eli's award-winning choral group called the Wiffenpoofs, and from Smith College the “Swithenpoofs.” In order to indoctrinate freshman into the Yale swimming fan club, Kiphuth sometimes set aside a section for freshman and their prom dates. The street that bordered the outside of the building was named “Broadway” and inside it felt like Broadway on the night of the Carnival.

The crowd was warmed up when the sons of Yale faculty members climbed aboard a Yale swimmer's body for “jockey races” up and down the pool. Although Yale didn't become co-ed until 1970, the coach arranged for a Beauty Queen contest judged by the Yale Art Department chief.

Kiphuth was always mindful of bringing the swimming community together. There was no club too small or country too far to promote the sport. Even the young kids that took swim lessons in the Faculty Childrens program on Saturday morning were included. They prepared for their annual Carnival performance with another Kiphuth innovation they experienced on Saturday mornings during their swim instruction. In order to enter the upstairs 50-meter pool, they had to traverse a long narrow hallway with a triangular shaped water sprayer. The boys were not permitted to wear bathing suits in the practice pool (neither were students and faculty during their swims in the pool) and straddling the sprayer down a long narrow hall so they were thoroughly cleaned before entering the pool. The boys did get to wear bathing suits for the Carnival!

Parents of swimmers bought their tickets and flooded into the sold out arena. The young kids sat in the rowing tanks in the Payne Whitney Gym, which served as a staging area, waiting their turn to perform. When they were called they were ushered down a hallway and out onto the pool deck like gladiators walking onto the floor of the Roman Coliseum. Looking straight up at more than 2,000 swimming fans was intimidating. The little kids raced over and back across the pool, while the older ones swam the length. Any race that was close — and most of them were — made a child feel as though they were wearing head phones with the volume at fevered pitch. The crowd noise funneled down from the stands onto the water with the acoustics of a fine opera house.

The coach invited the best local age-group and high school swimmers to battle in individual races, relay races and determine who were the fastest swimmers in Connecticut. It became a tremendous honor to earn the right, for example, to be one of the top six high school 200-yard freestylers in Connecticut. If you earned it, you would be invited to race the 220-yard freestyle, the yard equivalent to 200 meters. The finish line was created when a set of large blue flags were lowered across the water surface exactly 20 yards down the ninth length of the pool.

World records were one of the major drawing cards for spectators and a throng of press to cover them. In the 1930s, 40s, 50s, and 60s global standards could be set in various courses and distances. This presented many opportunities for Kiphuth to stage and promote “world record attempts” for the paying customer. For example in 1944 Adolf Keifer was the best backstroker in the world. His global standards included a 56.8 100-yard backstroke and a 2:19.3 200-meter backstroke. At the Carnival, he was featured in the pre-event promotion to make a world record attempt in the 400-yard backstroke.

Lionel Spence began the world record tradition in New Haven on April 1, 1932. His 200-meter breaststroke time of 2:44.6 was the fastest anyone had ever swum the distance. During the next 18 years the 200-meter breaststroke world record was broken 12 more times — seven of those swims were at Yale. In the 1943 Carnival alone 17 swimming standards were established!

For some of the spectators the clown diving served as even more of a highlight than cheering on a world record. Larry Griswold was one of the foremost clown divers in the world and could bring the house down on his own. The range of diving performances went from utilizing the normal 1-meter and 3-meter boards all the way to performing off of scaffolding that was built up above the three-meter board with a small trampoline on top…and beyond. How do you get higher than twice the height of three meter board or 20 feet? The diving shows progressed to having divers disguised as custodians fixing lights actually take the plunge from the 53 foot ceiling. Griswold became so successful and famous that on Nov. 13, 1951 he was featured on the Frank Sinatra Television Show with a trampoline serving as the water for a stage constructed swimming pool, along with a three-meter diving board. He was a huge hit in Kiphuth's Theatre and on Sinatra's nationally broadcast television show!

The Carnival became such a national phenomenon that legend has it the movie career of teenage swimming star Esther Williams was inspired in part by the spectacular water scenes that Kiphuth helped create at the Carnival. Williams missed the chance to compete in the Olympics in 1940 because World War II canceled the Games. Instead she moved forward in a professional career as replacement for Eleanor Holm in the Aquacade water show. From there she was discovered by a talent scout and offered a movie contract by MGM. From 1945 to 1949 Esther Williams' movies were annually among the top 20 grossing movies of the year.

By 1939, Coach Kiphhuth's Carnival had established New Haven, Connecticut as the number one location in the world to see World Records broken, as well as help inspire movie careers and provide the international community a focal point for swimming excellence. But he was only half way through his tenure as the Yale Head Coach that began in 1918. There was much to do to educate the world about training to swim fast and in the process educate this coach.

On a clear day, he neared the George Washington Bridge to cross the Hudson River. There was still four hours until he arrived in Washington D.C. and lots of time to consider all he had seen in the growth of the sport of swimming.

Note of credit due: Pete Kennedy, the Yale Archives with help from Terry Warner, Bruce Wigo and the International Swimming Hall of Fame and personal experience…swimming in the Yale Carnival at 9-years old…the loudest noise I had ever heard.

Chuck Warner is contributor for Swimming World Magazine and author of Four Champions: One Gold Medal. Chuck's latest book titled And Then They Won Gold, is now available for purchase.

Kiphuth's Ride to the Medal of Freedom: Part I

Kiphuth's Ride to the Medal of Freedom: Part II

Kiphuth's Ride to the Medal of Freedom: Part III

Kiphuth's Ride to the Medal of Freedom: Part IV

Kiphuth's Ride to the Medal of Freedom: Part V

Kiphuth's Ride to the Medal of Freedom: Part VI

Kiphuth's Ride to the Medal of Freedom: Part VII