Where and How Swimmers Fit In the Scheme of Endurance Athletes

Where and How Swimmers Fit In the Scheme of Endurance Athletes

By Vanessa Steigauf, Swimming World College Intern

Depending on the context, endurance doesn’t always mean the same thing. Especially between sports, the definition can vary quite a lot. Endurance in swimming can, therefore, be very different from endurance in sports like running, biking or skiing. While some runners compete in races that last more than 30 minutes or even several hours, a swimmer’s longest distance (at least in the pool) doesn’t get much longer than 20 minutes. Still, distance swimmers who regularly do the mile will justifiably argue that they are endurance athletes. But there are important differences between distance swimmers and other endurance athletes, including, for example, energy supply and the training needed for their specific events. Let’s take a closer look at what that means. What category of endurance do (distance) swimmers belong to?

What Is Endurance?

Generally put, it is “the ability to keep doing something difficult, unpleasant or painful for a long time.” That certainly applies to swimming, physically, as well as mentally. It is important to note that mental endurance is a key factor to performance and can definitely contribute to the endurance of any athlete. Nevertheless, we will stick to the physical aspect of endurance for the purpose of this article.

Some physical aspects that determine endurance are:

- Efficiency of energy systems

- Aerobic capacity (VO2 max)

- Lactate threshold

- Muscle strength and power

- Muscular endurance

- fatigue resistance

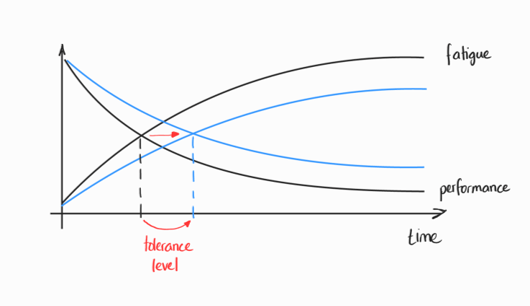

Fatigue is one of the most important limiting factors of endurance. During a race or general exercise, the level of fatigue inevitably rises while your performance decreases.

Photo Courtesy: Vanessa Steigauf

How To Train Your Endurance

To improve endurance, an athlete’s goal is to push the “tolerance level” as far to the right as possible. To do so, we need to flatten the curve of fatigue so that more time passes before we “hit the wall” and our performance significantly decreases. Our initial starting point of fatigue and performance is determined by genetics, mental grit and training history. But the course of both curves, fatigue and performance, is highly trainable. In practice, we therefore want to do anything that makes us better at resisting fatigue.

The best way to do so, is to have a solid base of endurance at any point in time, but especially to build it during the first weeks of practice each season. This base is what can make an important difference at lengthy championships toward the end of the season. When everyone gets super exhausted as the meet progresses, you can be the one who is able to push on and go faster.

Resisting fatigue involves endurance in several body systems. The most important ones are:

- Cardiovascular endurance

- Muscle endurance

- Aerobic endurance

- Anaerobic endurance

While cardiovascular and most of aerobic endurance are general types of endurance, anaerobic and muscle endurance are rather specific.

Cardiovascular Endurance

… involves the ability of your lungs, heart and circulatory system to transport oxygen to where it is needed in a fast and efficient manner. It can be trained generally, through other sports like running or aerobic workouts. But especially in swimming, a great portion needs to be done in the water. This is due to the fact that as swimmers, we have an additional factor that makes us differ a lot from other endurance athletes: we can’t breathe whenever we want. Our body needs to get used to the lower oxygen supply and making efficient use of the limited oxygen available. By building capillaries and producing mitochondria in those muscles where oxygen demand is high, we can get the oxygen-rich blood to where it is needed and can make the best use of it while swimming.

Muscular Endurance

… is the ability of a muscle or group of muscles to exert a force over a prolonged period of time. This is achieved through training in the weight room (general exercise) but also by resistance practices or longer intervals at race pace in the water. These types of practices help us to make better use of the energy supplied in forms of ATP and increase the muscle fiber recruitment by the nervous system. Especially the latter is accomplished by many repetitions of the same movement pattern at a low intensity. Even if that might sound boring for some of us, it means that long sets of low intensity swimming are crucial for not only distance swimmers, but sprinters as well.

Aerobic and Anaerobic Energy Supply

… are key principles for understanding how our body supplies the energy for all these strenuous practices that build our endurance. Sports like distance running, skiing or biking rely mostly on aerobic capacities. But swimmers get a great share of their energy from an anaerobic energy supply.

It is known that running 10km relies on aerobic energy supply for around 97% of the effort; a 5km is 95% aerobic; and a 3km is 90% aerobic. After that, we can see a huge drop: 1.5km needs 80% aerobic energy supply and 800m only 60%. The other part of the energy is supplied anaerobically. That means, for shorter races, anaerobic energy supply is exponentially increasing. Because swimming covers mostly distances around one, two, five or a maximum of 20 minutes, it is heavily anaerobic.

Where Does The Energy For Endurance Performances Come From?

Energy supply during exercise has essentially three different stages. The first 15 seconds are fueled by something called “direct phosphorylation.” Our cells don’t need any oxygen for that. All that is required is a molecule called creatine phosphate (CP) to generate ATP. We can basically use what’s already there to get through the beginning stages of our race. For the next 30 to 40 seconds, our cells switch to a mechanism that still doesn’t require oxygen to generate energy, but now uses glucose readily available in our cells. This is when you use the energy you got from the granola bar you ate before practice (or whatever filled up your glucose storage).

The two beginning stages of energy supply did not require oxygen and are, therefore, anaerobic. If you exercise for longer than that, in every race that’s longer than a 100, your body reaches out to its aerobic energy supply through mitochondria. Now, oxygen is needed to make ATP out of sources like glucose, amino acids and fatty acids. This produces most of the ATP used during your longer practices.

In a race, when you want to go really fast, you can’t rely only on this aerobic energy supply. It is way too slow and wouldn’t get you enough energy to go your maximum speed. Therefore, anaerobic energy supply pathways jump in. Their initial reservoirs are used up when you are 40 seconds into the race. Your cells then produce lactic acid as a byproduct to keep up with the high energy demand. Unfortunately, this lactic acid accumulates faster than your body can get rid of it. Too much of it creates an unfavorable environment for further energy production. This is what causes the tight and sore feeling in your arms and legs throughout the race.

What Makes Swimmers Very Special Endurance Athletes

Energy supply is the part where endurance swimmers differ most from endurance runners, for example. Runners race for hours and can get most of their energy from aerobic pathways and don’t accumulate quite as much lactic acid as a swimmer does during their race. Their goal during practice is to optimize the aerobic pathway of energy supply. Swimmers, on the other hand, need to work a lot more on their anaerobic capacity to prepare for racing, as it serves as a complement to the aerobic capacity. By building a high tolerance to lactic acid, you basically shift that point of fatigue we saw in the graph earlier to a later point in your race. You push back the point at which your body can’t keep up with lactic acid removal anymore and therefore build a higher resistance to fatigue.

The Base You Build Your Endurance Castle On

Keep in mind that swimmers also need a high level of aerobic endurance. Your aerobic capacity is the base that you built all your anaerobic endurance on. Think of it as a solid castle of anaerobic endurance you want to build. You won’t make it through a demanding swim season without a stable base. This aerobic base doesn’t only help you through your races. It also carries you through strenuous practices from day to day by helping you to recover faster.

Another benefit of a strong aerobic base is that it can facilitate re-uptake of the once toxic lactic acid. Your cells can then actually use it as fuel for more energy production. And who doesn’t want to get an extra boost mid-race by being able to feed off of previously produced waste products of energy production. It’s a true superpower when you are able to push even harder on your last 50, feeling a sudden burst of energy coming out of nowhere.

Build Your Own Superpower

And you now know, this energy is not coming out of nowhere. It comes from the deliberate practice and the many hours you spent in and out of the pool. This dedication built your base of endurance that fuels your important races at the end of the season. When everyone gets tired and can’t push any further, you can go harder. Understanding the principles of your endurance, where it comes from, and how you train it, is a powerful tool. It can help you guide your practice in the right direction. It’s time to “get comfortable being uncomfortable” in practice. Now you know that as a swimmer, you need to spend a lot of time outside your comfort zone, aka the aerobic energy supply, to be successful.

All commentaries are the opinion of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of Swimming World Magazine nor its staff.