When All Hailed to Michigan At the 1995 NCAA Champs; How a Team For the Ages Rallied After Relay-Card Snafu

Legendary Lookback: When 1995 Hailed to Michigan and a Team For the Ages

Despite not swimming the men’s 400 freestyle relay—due to a clerical error on the official relay card and a subsequent disqualification—the University of Michigan proved that it could win NCAAs by putting an emphasis on distance swimming.

*******************************

Jon Urbanchek knocked on the hotel-room door of Gustavo Borges, his mind occupied and a rare degree of worry creeping into his choice of words.

It was the 1995 NCAA Championships, and Urbanchek had just gotten a dreaded phone call during the midday break between the final two sessions. Michigan had set the top time in prelims of the 400 freestyle relay, but after a snafu on the relay cards, it had been disqualified. (It was brought to the officials’ attention that Borges swam the anchor leg of the relay although Michigan had listed Chris Rumley as the anchor on the official relay card. A special officials’ meeting was called later that afternoon, which confirmed the disqualification.)

The Wolverines carried a secure lead into the final night session at the Indiana University Natatorium. But spotting their chasers 40 points presented the first bobble of the week. And before he called his team together that night, a fuming Urbanchek wanted to talk things over with his senior captain.

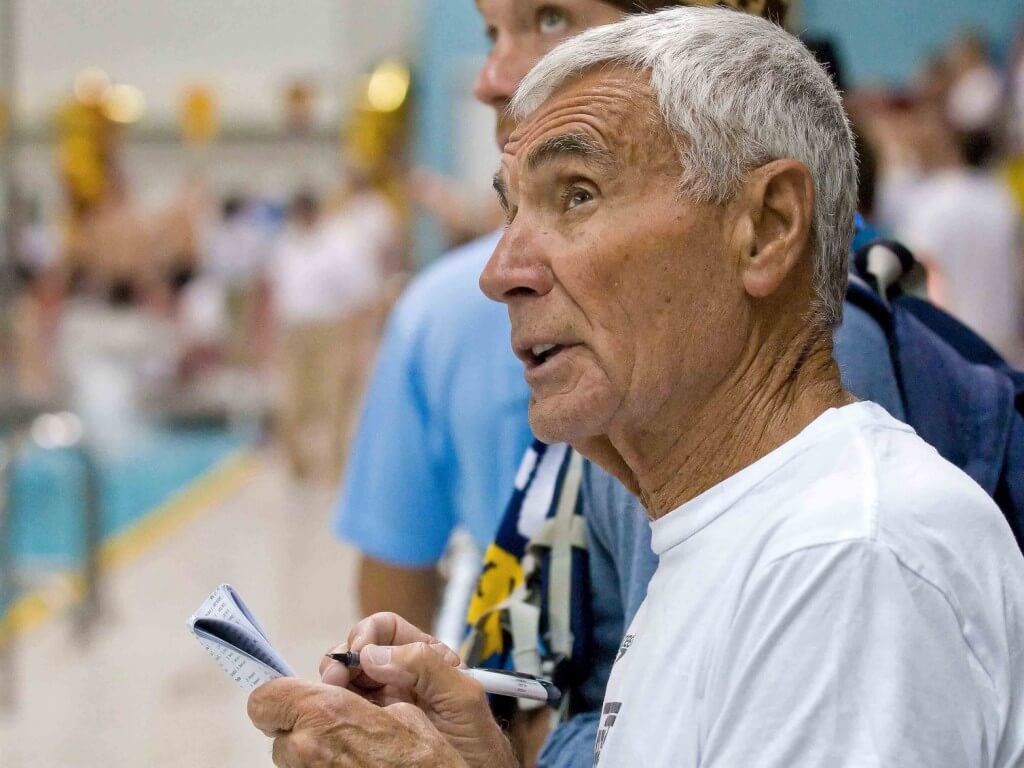

Photo Courtesy: Tim Morse

Urbanchek didn’t get very deep into the conversation before Borges caught him and set things straight. “I said to myself, they don’t know yet,” Urbanchek said recently. “Gustavo was a captain, so I went into his room, and said, ‘Let me talk to you.’ Well, bad news travels fast. Gustavo put his arm around me and said, ‘Jon don’t worry, I already had a meeting with the team.’ He said, ‘Don’t worry about it, we’re all going to swim a little bit better in our events to get the points back.’”

The final-night DQ did little beyond add a final twist to a triumphant tale. It also united the narrative threads behind Michigan’s national championship—among the leadership by Borges, the team culture that the Hall of Fame coach nurtured and the top-to-bottom contributions that would fuel the title.

When all was said and done, the Wolverines finished 86 points ahead of Stanford, the culmination of three straight top-three NCAA finishes and Michigan’s first title since 1961. As much as three titles each from Borges and Tom Dolan would stand out, the fact that 14 of the 15 Wolverines who traveled to Indianapolis scored points remains a more salient summation.

So is Urbanchek’s defiant proof of the concept that distance prowess could lead to a national title: “We’re making a statement by not swimming the 400 free relay,” he told the media after the meet. “We specialize in distance. Let it be a good example for others—you can still win the NCAAs without putting emphasis on the sprint events.”

HISTORY, IN SO MANY WAYS

Dolan was a sophomore in 1994-95, but he knew the history. Michigan had once dominated the national scene, culminating at the 1961 NCAA Championships, with Coach Gus Stager’s Wolverines winning their fourth national title in five years. While their dominion over the Big Ten was restored in the 1980s—the 1994-95 squad won the conference championship for a 10th year running—national power had shifted. Since Doc Counsilman’s Indiana teams of 1968-73, the NCAA swimming title had resided exclusively in the Sunbelt—in the SEC, in Texas, in California. It had been so long since Michigan had been on top of the NCAA that one of those swimmers in the late 1950s and early 1960s was a young Hungarian kid named…Jon Urbanchek.

Photo Courtesy: Tim Morse / Swimming World Archive

The composition of Michigan’s roster also didn’t fit the typical title-contender ideal. Borges was a versatile, all-purpose freestyler. But the bulk of the stars were middle-distance guys in freestyle and the 200 strokes. The prevailing wisdom was that NCAA titles went to teams packed with fast men who could win relays and forsake the longer events.

Urbanchek thought differently. He made it known to his swimmers, at an institution with a proud academic reputation, just how many conventions they were flying in the face of. And they embraced it.

“From a historical perspective, we were well aware of having the opportunity that year, even to start the year, of helping bring Michigan to the top again, the uniqueness of that story that Jon swam on that last team and now was coaching,” Dolan said. “None of that was lost on us. We very much appreciated and cherished playing a role in that story.”

Talent wasn’t an issue. The Wolverines would produce seven Olympians at the Atlanta Games the next year: Borges (Brazil), Marcel Wouda (Netherlands), Derya Buyukuncu (Turkey) and Americans Dolan, Eric Namesnik, John Piersma and Royce Sharp. Piersma, Dolan and Rumley were part of a tremendous class that graduated high school in 1993 and raised the level in Ann Arbor upon their arrival.

“The atmosphere at Michigan was intense,” Piersma said. “I don’t want to say it was intimidating, but Namesnik was there and Marcel Wouda was there and we had a lot of international guys, and there were some really fast people. If anything, it’s motivating. Everyone around you is racing. Practices were fun, but they were intense.”

THE MAN IN THE MIDDLE

The glue holding it together was Urbanchek. Beyond his technical prowess, Urbanchek understood how to mesh all those egos and personalities.

Urbanchek had taken over Michigan in 1982-83. Things got worse before they got better, dipping as low as 25th at NCAAs in 1986. But he rallied them to third by the end of the decade. They were a distant runner-up to Stanford in 1993, but with the Dolan-led class incoming, there was a sense of progress. The difference, as much as talent, was culture.

Urbanchek, now retired and in his 80s, describes it as instilling the value of, “I’m going to do this for Michigan; I’m not doing this for myself.” Many of his swimmers still echo that.

“I think it’s hard to put words to what Jon Urbanchek was able to do,” Piersma said. “He was a mentor, he was a great coach, he was a comedian, he had a big heart, and he could be that guy for you as a somewhat homesick freshman or sophomore. He somehow made it really easy to race each other.”

“Jon knew that everybody had their own pathway,” Dolan said. “How each individual swimmer was wired couldn’t be forced upon everybody else. Everybody had to find his own unique pathway, which then would allow the team to be successful. What Jon did really well was find those right levers and push those right buttons in all those athletes.”

With age, Dolan has come to appreciate the subtlety in Urbanchek’s approach. That team was so competitive that it struggled with active recovery or just-get-em-done sets. The ambience at practice could occasionally combust into toe-to-toe arguments. Much as Urbanchek is remembered for his humor, it was applied tactically. Sometimes, it would lighten a lesson, a pat on the back to distract from a kick in the seat. But just as often, with alpha males constantly hard on themselves, Urbanchek would diffuse tension with a ridiculous quip that wouldn’t fail to break through even the hardest exteriors.

“It just worked,” Piersma said. “It was this magic that he had. Maybe it was his attitude, but he was just a really incredible coach.”

THE ROAD TO INDY

One of those motivation tactics was one that Dolan, the occasional glutton for punishment, was on board with. After a winter training trip in early 1995, a beat-down Michigan squad visited Stanford for a dual meet. It would be their only loss of the season, a 150-146 setback.

Among the challenges that Urbanchek laid before Dolan was a quick turnaround from the 1000 free to the 200 backstroke, taking on then 100 back American record holder (and eventual double NCAA champ) Brian Retterer. The loss sent a message to Dolan & Co., about what losing to Stanford felt like, but also of what performing when not at your physical best takes.

“I vividly remember the Stanford dual meet and being so angry that, as a whole, we didn’t swim well, and so angry that we lost,” Dolan said. “That was kind of a game-changer for me.”

At NCAAs, the statement of Michigan’s depth was instant and impressive. Borges won the 200 free in 1:34.61, one of three Wolverines in the A-final. But they were so dominant that Borges wasn’t required to win the 800 free relay, with Piersma, Rumley, Owen Von Richter and Dolan handling matters by a second-and-a-half over Stanford, and Dolan rallying the team on the anchor.

Tom Dolan was one of the veterans on the 2000 U.S. Olympic Team.

Dolan won the 500 free, trouncing the American, U.S. Open and NCAA records set a year earlier by Chad Carvin of Arizona. In beating his records by 2.84 seconds, Dolan also bested Carvin in the race by 3.61 seconds. Dolan did the same in the mile and the 400 individual medley, another 2-plus-second routing of the record. Borges won the 50, 100 and 200 free, ensuring the Wolverines won all five freestyle events.

Complicating his meet was a quick return from the Pan American Games, held that March. Borges won the gold in the 100 free and 200 free there plus three relay silvers, then booked it from Mar del Plata, Argentina, to Ann Arbor four days before NCAAs began. Teammates recall that devotion and his leadership as instrumental to what transpired in Indy.

But the real strength was depth. All but one of the NCAAs’ delegation scored, tallying points in every event save for the disqualified relay and 3-meter diving. Dolan thinks back to swimmers who looked like long shots to make NCAAs ahead of Big Tens, but who ended up scoring points.

“It was about guys who found levels of success that you’d never think were possible that weren’t your top guns like a number of us were,” he said. “And I think that was a credit to Jon, too. Those swims at Big Tens of guys who weren’t supposed to make it to NCAAs were just as big for our team as individual wins in NCAAs.”

Dolan, Piersma, Rumley and Von Richter gave Michigan four of the top five in the 500 free. Von Richter, Sharp and Wouda did the same behind Dolan in the 400 IM. The blow on the final day of the relay was cushioned by the mile to start that session. Dolan won it, with Von Richter fourth, Rumley fifth, Wouda seventh and any possible turmoil exorcised.

“We were more narrowly focused than we would’ve been before to perform on that last night of finals, and not only did we not let that (relay DQ) negatively affect us, but the opposite: Use it as a springboard to swim better than you thought you could, and let it make you angry,” Dolan said.

“I was a big believer, and we talked about it in the locker room: Get angry. Everyone should be angry. That didn’t go according to plan, so let that sink in and use it…. Let that be the fuel. And that’s kind of where everyone went.” Sharp was the runner-up to Retterer in the 200 back, negating what Stanford thought might be an edge. Jason Lancaster made both fly finals and was second in the 200 IM, a spot ahead of Wouda.

“Everyone collectively stood up and raced, and we scored a ton of points,” Piersma said. “It was just incredible!”

* * *

Dolan is clear on the impact that season had on him. Working for the team, he came to understand what he could do, how far he could push his performance and mentality. It’s a straight line for him between Indianapolis and what he achieved 15 months later in Atlanta, winning Olympic gold in the 400 IM. The way others raised their level over that period provide supporting evidence.

But that season at Michigan stands out in another way for Dolan.

“It will always go down for me as the most fun I had in swimming,” he said. “Even ahead of winning gold medals and breaking world records in long course meters—those are incredible experiences at the international level and having the American flag on my suit. But I have to say, the most joy in the sport I got was certainly being part of the team representing Michigan and finally winning in ’95.”

Great stuff, thanks for the memories. I still have that meet saved on VHS! Now, if I can only find a way to watch it…