Out of the Pool: Markus Rogan on Performance Psychology and Finding Identity

Out of the Pool: Markus Rogan on Performance Psychology and Finding Identity

The life of a swimmer extends well beyond the pool. In a new occasional series, Out of the Pool, we talk to former swimmers who’ve gone on to excel in their post-athletic careers.

Markus Rogan was on the verge of this third Olympic Games when he felt safe declaring that he no longer enjoyed swimming. It’s a testament to the Austrian’s journey that he still had one more Olympics left in him after that.

The silver medalist in the 100-meter and 200-meter backstroke at the 2004 Athens Games, Rogan had a complicated journey through the sport. The Stanford grad competed on the international stage for more than a decade, emigrating to the Washington D.C. area in high school from his native Austria. He credits swimming with opening the door for many of the aspects of his life he now enjoys at age 38.

But they came at a price. And the emotional weight of that journey is what led Rogan to a post-athletic career as a psychologist.

“Ignoring symptoms makes you sick,” Rogan’s website reads. “Facing them makes you come alive.” Specializing in “experiential performance psychology” in Southern California, Rogan works with clients who are athletes and some who aren’t. He works in clinical settings and as a sports psychologist, focusing on performance and the challenges athletes face. As he says, “Most of my patients are athletes, and most of my athletes are patients.”

Swimming World caught up with the four-time Olympian and world-record holder recently to discuss his post-swimming career and how his achievements in the pool informed his journey.

(The interview is lightly edited for clarity.)

Swimming World: What is it that drew you to becoming a psychologist?

Markus Rogan: I can tell you specifically the moment. My psychologist was Ken Ravizza, who has since passed but was an amazing psychologist who also worked with the Cubs when they won the World Series for the first time. We were in his backyard and he did this amazing exercise where he gave me these buckets and he asked me about all the pain that’s happening in my life. For each pain I mentioned, he gave me a brick and wrote how to describe the pain on that brick, and put it in the bucket. And he had me walk around his yard with these buckets full of bricks. And he said, ‘you know, carry them as long as you want. You’ve been carrying some of these bricks for decades. So just keep carrying them. You can be in my yard as long as you want.’

So I saw two things for the first time in that moment. One is that pain happens. We all have traumas and fears and abuses and all these things happen in our lives, but the suffering is optional. Especially after the immediate trigger or trauma or abuse happens, after that, the suffering is in your mind and your heart. There are real scars, but you can do something about it. That was just a real big relief for me, and it was so helpful that I’d love to help others in this way. So I decided right then, hey, this is what I want to study.

SW: In listening to your TED Talk and the way you’re open about carrying your traumas, how much of your approach with clients is looking to provide some of the messages that maybe you wish you had heard earlier?

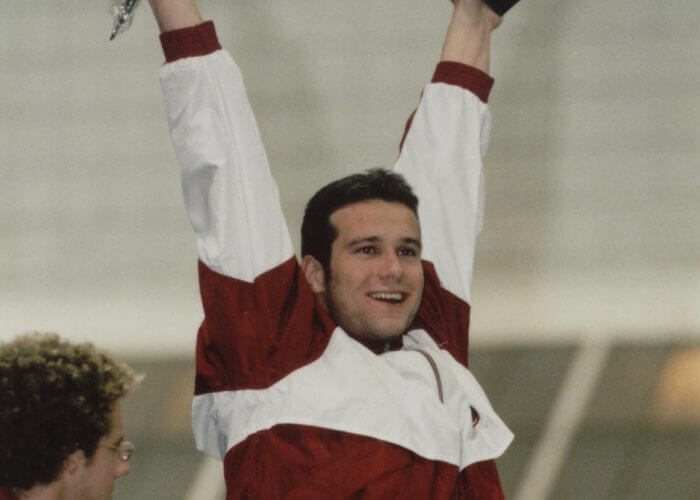

Photo Courtesy: Tim Morse / Swimming World Archive

MR: I think early on, I tried to treat my younger self. And I think that’s a mistake that a lot of therapists make. And I don’t think I can help anyone that is experiencing pain that I don’t have any idea what it feels like. I have to do my clinical due diligence and say, I’m sorry, I can’t help you. That’s humbling and embarrassing sometimes to say. But I know I can help people who have similar pains or similar enough pains that I had. Specifically, one thing that I can really connect with is some athletes who really, really crave that external validation, the athletes who are swimming, in our case, or fighting or playing for the next big-money contract and who get caught up in that validation from the outside.

SW: You talk a lot about the identity piece – of how athletes define themselves as athletes and by their accomplishments. How much do you think that identity challenge is part of mental and emotional struggles we see in athletes?

MR: Absolutely, and I think there’s a very specific reason for that: When we’re teenagers, a normal teenager asks themselves, ‘who am I? What is good about me? What is not good about me? What is socially acceptable? Not socially acceptable? Unappealing?’ These are painful questions of identity. Athletes in general, but good athletes especially, get a ready-made identity handed to them. Oh, you’re a good swimmer. Case closed. (In my experience) I have great social connections, I could become part of groups just by being a great athlete. The reason I can speak English is because I could swim, because when I moved to the U.S. when I was 14 years old, I had actually failed English in Austria and I couldn’t speak a word. But guess what, when I moved here, I was ESL (English as a second language) and the swimmers at that high school saw, ‘hey that kid can swim; let’s teach him English so he doesn’t fail his classes.’ I had the great advantage of learning English.

Athletes don’t have to go through the painful teenage process of finding their identity because they have an identity that’s handed to them in the form of achievement. But achievement is more than just, you’re good at something. It gives you a full picture. Of course you do get a little – you’re great, I’m a swimmer, I don’t have to worry about what’s my sexuality, what’s my gender identity, what’s my motivation for living, what’s my motivation for dying – all these painful, uncomfortable, awkward questions that I never had to have.

But then of course, the questions don’t go away. They linger, and then while the other teenagers figure it out by their mid-20s, we’re getting medals, we’re getting money, we’re not going to listen to those questions. We’ve got more medals to win and more money to make. So then the questions catch up to you. And you see this all the time. Why do grown men, like 30-year-old athletes, behave like teenagers? Because that’s where they are.

SW: I guess it’s a question that you can’t escape, ultimately.

MR: You’d better answer it. You could of course have so much money that no one ever asks you, or have so much fame that no one ever asks you. People don’t push people that they want to have sex with or get money from.

SW: In your process of transitioning away from an athletic career, do you ever think how your career might have been different if you had this perspective earlier?

MR: I think I would’ve abused less drugs and alcohol in my 20s. I would’ve been a lot more open and vulnerable in relationships, and I would’ve been less obsessed with my outside image. I think I would’ve been a better friend, brother, man, son, lover. But maybe, and this is a painful question I can’t answer, maybe I would’ve been less of a good athlete.

SW: You’ve worked not just with clients in a clinical setting but also athletes and teams, among them the 2016 Brazilian Olympic swim team in Rio. What can you say about your work with them?

Photo Courtesy: Tim Morse / Swimming World Archive

MR: The fascinating thing about that was when the soccer team, the loss at the World Cup in 2014 7-1 to Germany, that’s when the pressure really, really shifted to the Olympic team. I’d like to claim that I’m this great psychologist that really helped them, but what it really was was them realizing, ‘wow, the pressure is real.’ A lot of athletes will say, ‘I can handle the pressure. Ah, no problem.’ Or deny, deny, deny it. And then they get to the Games or the World Cup and then they get knocked out. As much as I’d love to say I helped them, it was much more them realizing it.

SW: You talked at the 2008 Olympics about ‘hating the sport’ at that point in your career. How prevalent of an issue do you think that is in athletes, and would you want to see people in the sport coaching in a way so as to be aware of and try to help swimmers avoid feeling that?

MR: I think that was just a moment of what today we understand as burnout. And for me, it was chasing external rewards instead of just enjoying the sport. That’s one of the things that Ken taught me, is what do you actually enjoy and do more of that, and the performances will follow. Yes, I think coaches should be more aware, but the other side to it is, if you make everyone enjoy it, you’re going to have a great enjoyable practice, but not everyone’s going to get better. At the end of the day, I want to be careful that sometimes what I have trouble with with many of my colleagues is that they say, we’re coddling over results. At the end of the day, professional sports are extremely hard and painful. Maybe the goal is to make everyone feel good, but that’s a different goal than achieving performance. To say, oh a great performance will feel good and you’ll feel good with a great performance and all you have to do is be happy, no, that in my opinion is nonsense. Sometimes you have to suffer, and painfully suffer to achieve something. There’s no touchy-feely psychology tricks that can make you not suffer.