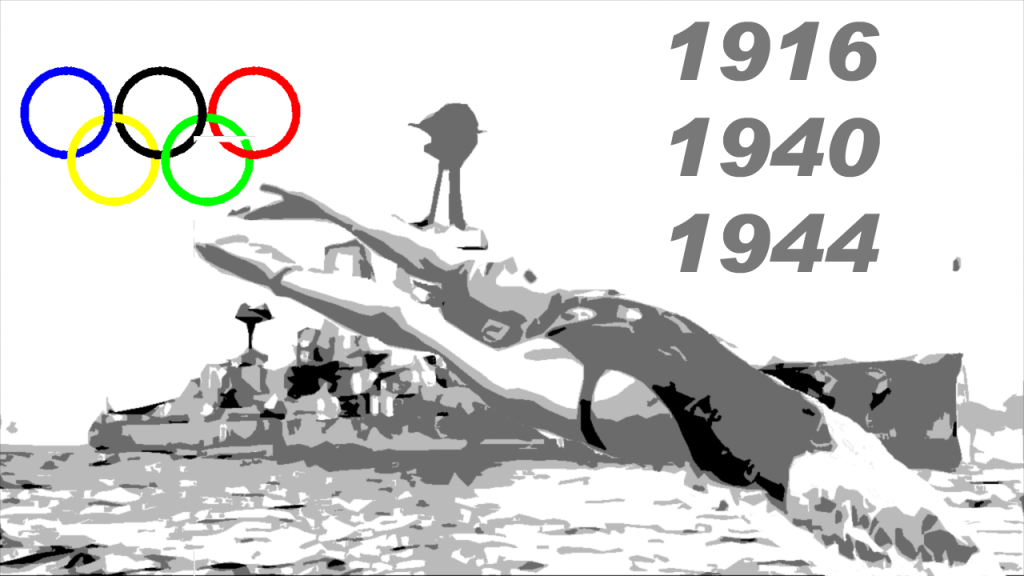

Three Olympics Were Casualties of War; Three Swim Stars Lost Chance for Olympic Glory

Feature by Jeff Commings

PHOENIX, Arizona, May 26. WE remember on this Memorial Day weekend the lives of those who fought valiantly for the United States in military action. The toll that the two World Wars took on the global population extended beyond the battlefields, with the Olympic Movement taking a back seat to bombs and tyranny.

Three Summer Olympic Games never happened because the world was busy fighting. World War I forced the cancellation of the 1916 Olympics, originally set for Berlin. World War II lasted longer, causing the International Olympic Committee to shut down the 1940 and 1944 Games.

Several thousand athletes lost their chance to stand on the top of the Olympic podium with the cancellation of these three Olympics. Some chose to fight in World War II when it became clear that they could not represent their countries athletically, earning honorable distinctions for their service. Others found a new life in the 1940s, becoming more famous than any Olympics would have made them.

Though each one of those athletes who lost out on a chance to compete in 1916, 1940 and 1940 deserve attention, we’re highlighting three of them today. Each of these American swim stars have become household names in the swimming community, both for their swimming accomplishments and lives outside the pool.

Duke Kahanamoku

“The Duke” could have been the first four-time swimming Olympian had the 1916 Games been held. As the 1912 champion in the 100 freestyle, he was pegged to win easily in 1916. Though he would have been 26 at the time, considered ancient by those standards, his dominance was undeniable.

That was evident by the time the 1920 Olympics arrived. Kahanamoku never stopped training and never stopped winning while World War I ravaged in Europe. He was keeping fit as he traveled the world as a popular exhibition surfer. At the 1920 Games in Antwerp, he nearly cracked the one-minute barrier in the 100 free with a 1:00.4 in the final, but that race was reswum after protest. Kahanamoku’s 1:01.4 in the official final tied his own mark.

At the elderly age of 34, Kahanamoku qualified for the 1924 Olympic team, but by this time had been supplanted by the arrival of 20-year-old Johnny Weissmuller. Amazingly, Kahanamoku’s time in winning the 100 free silver medal was exactly the time he swam officially to win gold in 1920.

Weissmuller, George Kojac and Walter Laufer prevented Kahanamoku from competing in the 1928, shutting him out of the opportunity to swim in a fourth Olympics. Kahanamoku did return to the Olympics in 1932, playing water polo for the United States.

These days, Kahanamoku’s swimming accomplishments pale in comparison to the impact he had on increasing surfing’s popularity. If you need proof of this, visit the bronze statue of him on the shores of Waikiki Beach. There are no Olympic medals around his neck. Only a surfboard stands behind him.

Adolph Kiefer

Adolph Kiefer is a household word among swim families, more for his successful company selling swim equipment than his years dominating in backstroke, but the two are intertwined.

Would Kiefer have been able to start such a business without first becoming one of the most famous swimmers in the late 1930s? Not likely. For a span of about seven years, Kiefer never lost a backstroke race. That included the 1936 Games in Berlin, where he won the 100 backstroke in 1:05.9. No one was able to beat that time at the Olympics until 1956.

It’s possible that Kiefer could have lowered his Olympic record a couple more times, if the 1940 and 1944 Olympics had not been canceled by the events of World War II. When 1940 came, Kiefer was 22 years old and still in the prime of his swimming career. That was evident when he blasted a 57.9 in the 100-yard backstroke at the indoor nationals, shaving nine tenths off his own record. One wonders what Kiefer could have accomplished in the 1940 Games, had he been given the chance.

“That (cancellation of the Olympics) is sad for me to remember because I was still swimming and breaking records,” Kiefer told Swimming World. “But at least during the war we still had the AAU nationals. I was able to leave the Navy to defend my titles.”

It is Kiefer’s service in the Navy from 1941 to 1946 that he made an invaluable impact on the course of American lives that still resonates today. Instead of fighting on the front lines, Kiefer taught thousands of officers how to swim and set new guidelines for teaching soldiers how to swim correctly. His success carried over to state and national appointments as the go-to guy for advocating swimming proficiency.

With his amateur status gone, Kiefer decided to make his way in the world by starting his own business. In 1947, Adolph Kiefer & Associates opened in his hometown of Chicago and sold equipment and apparel to the world.

Though he owns just one Olympic medal, Kiefer has become one of the most famous swimmers to ever take part in sport’s biggest event.

Esther Williams

One of the most famous entertainers of the 1940s was one of the fastest female swimmers of her time. But Esther Williams never got her shot to compete in the Olympic Games.

Williams’ star was just beginning to rise in 1939 when she set the American record in the 100-meter freestyle with a 1:09.1. The 17-year-old’s participation in the 1940 Olympics was not in doubt, and talk of a new Olympic star was already starting well before discussions of cancelling the Olympic Games began.

But Germany’s invasion of Poland stopped any plans to have an Olympic Games in London in 1940, and it also halted Williams’ Olympic dreams. Looking to earn a living like many young adults during wartime, she began modeling in 1941, thereby giving up her amateur status and losing any chance of competing in any future Olympic Games.

But dashed Olympic dreams turned into more than a decade as a Hollywood star in Billy Rose’s Aquacade and films featuring her in elaborate water-based performances. She would be named one of the top-earning actresses in Hollywood from 1945 to 1949.

Williams got her chance to appear at an Olympic Games, when she served as a commentator for the inaugural synchronized swimming competition at the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles.